Introduction

The Age of Antiquity is also known as the Ancient Era. It began from the beginning of recorded human history (around 3000BC), to the Early Middle Ages (around mid 400’s). In fine art, the term refers to the period of the beginning of Western civilization (around 4500BCE) up to the beginning of the Middle Ages (about 450 CE).

The term was first used by Renaissance writers. Studying the achievements of the past is key to creating magnificent future artwork. A tactic to explore the pieces of art was through looking and exploring ancient texts, ruins, unearth objects such as monuments, coins and statues.

The Age of Antiquity and in particular classical antiquity influenced Renaissance architecture, art and city planning. It also created a basis of the cultural movement named humanism.

In this pedagogical dossier, we will first introduce the origins of the movement, providing a brief historical and cultural context to its rise. Then, we will go into details about the specifics of the movement, based on colours, shapes, brushstrokes, perspective and more. Lastly, we will introduce 10 of the most famous paintings/sculptures over the era and provide 2 practical examples of activities that can be implemented for an art workshop based on Antiquity.

To summarize, in this dossier, you will:

- Learn the origins of the Antiquity movement,

- Discover some of its key figures and influencers,

- Explore the characteristics of Antiquity techniques,

- And more!

Background of the movement

Classical Rome

Ancient Rome refers to Roman civilization from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD.

In Rome, Italy, where many of the citizens lived among ancient and crumbling remains of old and long-dead civilization, the study of ancient cultures began. Antiquarians (scholars of the ancient world), started looking among the ruins for any possible clues related to the lives of previous and lost civilizations. At the same time, in the United Kingdom and in other parts of Europe, historians had the same mission – to discover their countries’ distant past.

As it can be seen in the photo above of the ruins at the Forum Romanum in Italy, up to today’s date there are ruins of ancient theaters, temples columns and arches in Italy and other Mediterranean regions. Many of these monuments are also located in Greece.

However, some argue that the maps and guides of the cities from the Middle Ages show that the citizens who were living during the Middle Ages did not understand the significant of these ancient monuments.

While most of the citizens knew the names of the famous antiquities, many did not know their original functions. Some famous antiquities are the Pantheon and the Colosseum, which can be seen below.

The Flavian Amphitheatre, much well known as the Colosseum was built in the 1st century AD in Rome. It was the largest amphitheatre in the Roman Empire.

The Colosseum was built by the Flavian emperors. Construction started at the initiative of Emperor Vespasian in 72 and was financed from the spoils of the sack of Jerusalem in 70. Many Jewish slaves, part of the spoils of war, worked on the enormous amphitheatre. After its completion in 80, it was consecrated by Emperor Titus, the eldest son of Emperor Vespasian. There were four gladiatorial schools in the vicinity of the Colosseum. The Colosseum was entirely intended for the games organized and financed by the reigning emperor. At the opening, Titus hosted games that lasted 100 days. According to tradition, in addition to many gladiatorial fights, the most astonishing spectacles were seen. There were fights between cranes and fights between four elephants. Nine thousand animals were slaughtered. Women also acted as wild animal fighters.

In the 12th century, the ruins of the amphitheatre were converted into a fortress of the Frangipani family. The important Roman families, often including the Pope, regarded the Colosseum as a quarry from which easy building material could be obtained for their newly built churches and palaces. For example, all the marble was removed and reused in new buildings or simply burned to obtain lime. The iron with which the blocks of stone and marble were secured was also in demand. This looting only came to an end in 1749 when Pope Benedict XIV recognized the historical value of the Colosseum and banned its further use as a quarry. He dedicated the Colosseum as a church in memory of the Passion of Christ and built a Station of the Cross inside. Subsequent popes allowed the Colosseum to undergo further restoration and archaeological investigations. Although the Colosseum no longer has its original dimensions, it is still an imposing whole and attracts thousands of tourists every day. In modern times, part of the wooden arena floor has been restored.

On July 7, 2007, the Colosseum was named one of the New Seven Wonders of the World.

The Pantheon is so well designed and so simple, that it is still almost entirely intact. This is all the more amazing when you consider that two different popes had its roof metal removed for other uses, leaving it unprotected for centuries. Built by Marcus Agrippa, son-in-law of the Emperor Augustus, the temple was dedicated to the most holy planetary gods, with the dome representing the firmament, and its opening representing the sun. Damaged by fire in AD 80, it was rebuilt in the reign of Hadrian (AD 120-125); the brickwork of this period demonstrates the technical mastery achieved by the Romans. Early Christian emperors forbade using this pagan temple for worship, and it was disused until Pope Boniface IV consecrated it as a Christian church and dedicated it to the Virgin and all the Christian martyrs on November 1 in 609–the origin of the Christian feast of All Saints. The great dome rests on a cylinder of masonry walls, inside which are large, empty spaces. These voids, combined with the alcoves that surround its interior, allow for a lighter construction, while supporting the dome through strong arches.

The visual effect is that of three continuous arcades, and if you look at the rotunda from the outside, you can see the brick arches that absorbed some of the stress from the dome’s weight. Originally, these exterior walls were faced with fine marble, but over the centuries it has been removed.

The Romans of 1400 also were not aware of the full size and spread of an ancient city. The writings that had survived across Europe were not understood by scholars and historians. Renaissance scholars devoted their lives to finding the distant past. In Rome, residents turned up many of their long-buried marvels and found many antiquities, some under their vineyards, some under foundations for new buildings.

A statue discovered in 1506, made out of marble, of Laocoön and His Sons (also called the Laocoön Group), for example, proved to be a piece of art mentioned in the works of the ancient Roman writer Pliny. This statue is placed on public display in the Vatican Museums.

Historical and societal context of the movement

As antiquarians learned more about the values and practices of the ancient world, they began to adopt them as part of their own culture. For example, Renaissance architects such as Filippo Brunelleschi and Leon Battista Alberti examined, measured, and sketched the spectacular ruins of ancient buildings, seeking to understand how they had been built and used. They then adapted these classical forms in the designs of their own buildings, linking their own world with the great cultures of the past. Artists began to hold the art of Greco-Roman antiquity in higher regard, while previously during the medieval period, the focus was on Byzantine art.

On the left, an example of an artwork from the Byzantine art: one of the most famous of the surviving Byzantine mosaics of the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople – the image of Christ Pantocrator on the walls of the upper southern gallery, Christ being flanked by the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist.

Filippo Brunelleschi was an Italian architect, goldsmith, and sculptor. The first Renaissance architect, he also formulated the principles of linear perspective which governed pictorial depiction of space until the late 19th century. He is considered to be a founding father of Renaissance architecture.

Brunelleschi and Donatello were one of the first people who studied the physical fabric of the ruins in Ancient Rome. Brunelleschi developed his system of linear perspective after his observation and studies of Ancient Rome.

While in Italy, scholars were studying the antiquities of Rome, in England, Henry VII hired an antiquarian – John Leland to examine the English relics. There were attempts in England, to prove that the history of the nation is at least as ancient as the Italian and Greek ones.

Classical Greece

In the art, culture and architectural contexts, Classical Greece was in the period around 200 years, so around the 5th and 4th centuries BC in Ancient Greece. There are a number of architectural antiquities famous to this date that were built in this period. One of which is the Parthenon. Its construction began in the 5th century BC.

The Parthenon is a former temple on the Athenian Acropolis, which is dedicated to the goddess Athena. For a time, it also served as a treasury and in the final decade of the 6th century AD, it was converted into a Christian church, dedicated to the Virgin Mary. The Parthenon itself actually replaced an older temple of Athena, which historians call the Pre-Parthenon, which was demolished in the Persian invasion of 480BC. The decorative sculptures of the Parthenon are considered some of the high points of Greek art and it serves as a symbol of Ancient Greece.

This period was succeeded by the Hellenistic period.

Hellenistic art

After the death of Alexander, the Great, in 323 BC, and also the end with the conquest of the Greek world by the Romans, the expansion of the Greek influence began. The term Hellenistic refers to the expansion of Greek influence and dissemination of its ideas. There are many breath-taking artworks, also some of the best-known works of Greek sculptures, that belong to this period. One of the is Venus de Milo, which was discovered at the Greek island of Milos (on the left), 130-100BC, or the Winged Victory of Samothrace (on the right), from the island of Samothrace.

Characteristics of the movement

There are several characteristics that can help a viewer identify the traits of antiquities. Here are some of the most common ones:

Visual accuracy in sculptures:

Already more than 2000 years ago, the Greeks were building life-size, freestanding statues that attempted to mimic the human form at a time when other cultures had much more abstract and stylistic approaches. There were a number of core values that influenced them. One of which is their devotion to the study of the natural world. This commitment and interest required observation and experimentation, which led to a very realistic artwork style. Another important aspect was that due to the philosophies in Greek, the artwork was very idealistically realistic, meaning that they portrayed the ideal human. Furthermore, although it varied between genres, evidence was visible of harmony, balance and promotion in all the paintings and sculptures of the classical antiquity art.

Colours

Ancient Greek antiquarians used a four-colour palette, consisting of red, yellow, black and white. They used “blending” as a method of combining the colours and thus enriching their palette. A lot of the classical antiquity artworks were painted by artists, using a colour palette that included six colours: red, green, blue, yellow, white and black. Ancient Romans loved colour, which is also why many of the people wore bright coloured dyed (purple, red, green, grey, and yellow) clothes. Red was also one of the most popular colours in Roman wall art.

Furthermore, while most people assume that ancient buildings and sculptures were not colourful, this assumption is incorrect. They ancient buildings and sculptures were actually very colourful. The Greeks and Romans painted their statues to resemble real bodies, and often gilded them so they shone like gods. Their colours were demolished, as after the fall of Rome, for example, ancient sculptures were buried or left in the open air for hundreds of years, which caused for the paint to fade away.

Materials

In ancient Greece and Rome, people used marble (especially white marble) to make statues. They cut coloured marble in patterns to make hard floors that would last a long time. The art of Ancient Rome included architecture, painting, sculpture and mosaic work. Some luxury objects that were created using metal-work, gem engraving, ivory carvings, and glass are sometimes considered to be minor forms of Roman art, although they were not considered as such at the time.

Style

Classical Greek style is characterized by a joyous freedom of movement, freedom of expression, and it celebrates mankind as an independent entity. Some of these advances were brought about by the emergence of the Pre-Renaissance period whose early subjects were restricted to religious artworks called Pietistic paintings that also came in different forms such as illuminated manuscripts, mosaics and fresco paintings and were to be found in churches.

Classical antiquity influenced Renaissance architecture, art, and city planning. It also transformed the study of history and formed the basis of the cultural movement called humanism

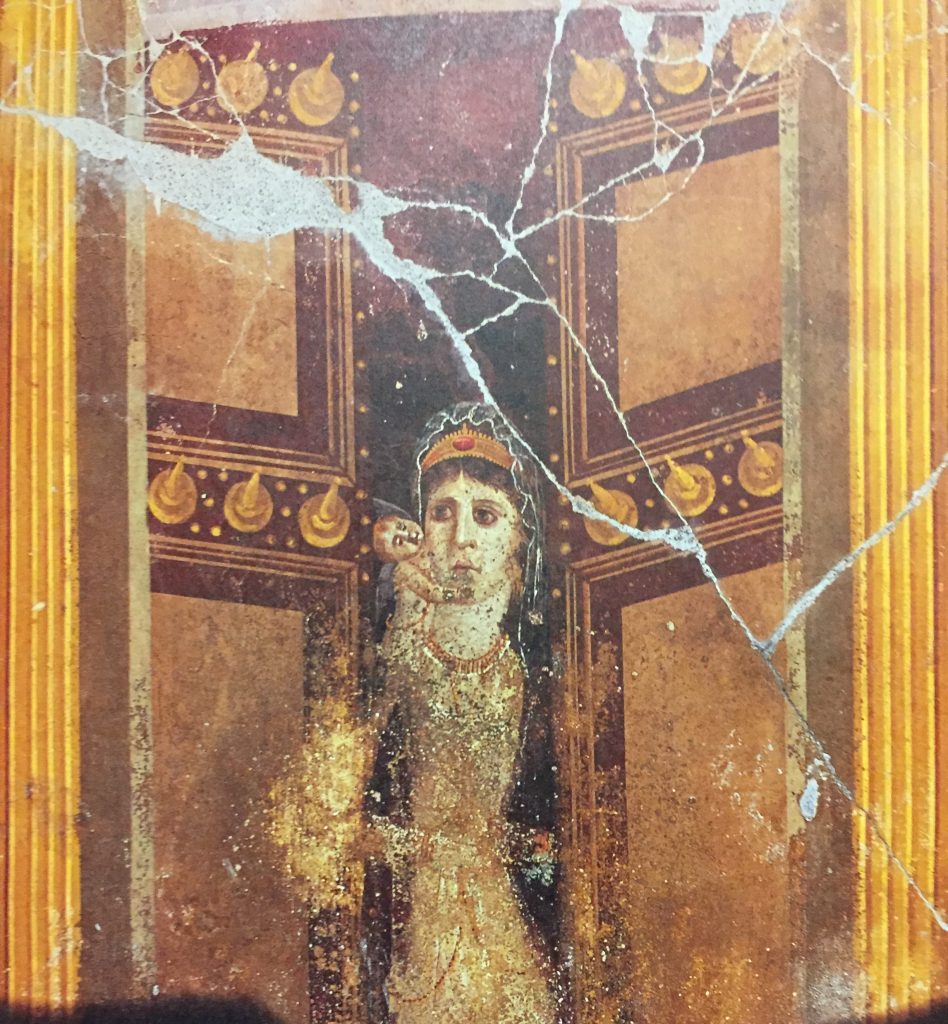

Pompeian styles

The Pompeian Styles are four periods which are distinguished in ancient Roman mural painting. The wall painting styles have allowed art historians to delineate the various phases of interior decoration in the centuries leading up to the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD, which both destroyed the city and preserved the paintings, and between stylistic shifts in Roman art. There are four main styles of Roman wall painting that have been found: Incrustation, architectural, ornamental, and intricate. The first two styles (incrustation and architectural) were a part of the Republican period (related to Hellenistic Greek wall painting) and the last two styles (ornamental and intricate) were a part of the Imperial period. The main purpose of these frescoes was to reduce the claustrophobic interiors of Roman rooms, which were windowless and dark. The paintings, full of color and life, brightened up the interior and made the room feel more spacious.

The First style, also referred to as structural, incrustation or masonry style, was most popular from 200 BC until 80 BC. It is characterized by simulation of marble (marble veneering). The marble-like look was acquired by the use of stucco moldings, which caused portions of the wall to appear raised.

The Second style, architectural style, or ‘illusionism’ dominated the 1st century BC, where walls were decorated with architectural features and trick of the eye compositions. This technique consists of highlighting elements to pass them off as three-dimensional realities – columns for example, dividing the wall-space into zones – and was a method widely used by the Romans. The second style retained the usage of marble blocks. The blocks were typically lined along the base of the wall and the actual picture was created on flat plaster.

The Third style, or ornate style, was popular around 20–10 BC as a reaction to the austerity of the previous period. It leaves room for more figurative and colorful decoration, with an overall more ornamental feeling, and often presents great finesse in execution. This style is typically noted as simplistically elegant. Its main characteristic was a departure from illusionistic devices, although these (along with figural representation) later crept back into this style. It obeyed strict rules of symmetry dictated by the central element, dividing the wall into 3 horizontal and 3 to 5 vertical zones. Black, red, and yellow continued to be used throughout this period, but the use of green and blue became more prominent than in previous styles.

Characterized as a Baroque reaction to the Third Style’s mannerism, the Fourth Style in Roman wall painting (c. 60–79 AD) is generally less ornamented than its predecessor. The style was, however, much more complex. It revives large-scale narrative painting and panoramic vistas while retaining the architectural details of the Second and First Styles. The overall feeling of the walls typically formed a mosaic of framed pictures. One of the largest contributions seen in the Fourth Style is the advancement of still life with intense space and light.

Imperial Art

Imperial art often hearkened back to the Classical art of the past. “Classical”, or “Classicizing,” when used in reference to Roman art refers broadly to the influences of Greek art from the Classical and Hellenistic periods (480-31 B.C.E.). Classicizing elements include the smooth lines, elegant drapery, idealized nude bodies, highly naturalistic forms and balanced proportions that the Greeks had perfected over centuries of practice. Augustus and the Julio-Claudian dynasty were particularly fond of adapting Classical elements into their art. The emperor Hadrian was known as a philhellene, or lover of all things Greek. The écor at the emperor’s rambling Villa at Tivoli included mosaic copies of famous Greek paintings, such as Battle of the Centaurs and Wild Beasts by the legendary ancient Greek painter Zeuxis.

Later Imperial art moved away from earlier Classical influences, and Severan art signalled the shift to art of Late Antiquity. The characteristics of Late Antique art include frontality, stiffness of pose and drapery, deeply drilled lines, less naturalism, squat proportions and lack of individualism. Important figures are often slightly larger or are placed above the rest of the crowd to denote importance.

We don’t know much about who made Roman art. Artists certainly existed in antiquity but we know very little about them, especially during the Roman period, because of a lack of documentary evidence such as contracts or letters. What evidence we do have, such as Pliny the Elder’s Natural History, pays little attention to contemporary artists and often focuses more on the Greek artists of the past. As a result, scholars do not refer to specific artists but consider them generally, as a largely anonymous group.

Pedagogical approach

Why is this theme relevant to adult learners?

Antiquity is one of the most important movements in art and cultural history. There are many breath-taking artworks, also some of the best-known works of Greek sculptures, that belong to this period. Classical antiquity influenced Renaissance architecture, art, and city planning. Brunelleschi developed his system of linear perspective after his observation and studies of Ancient Rome. This movement was a turning point in art history that learners cannot bypass.

What are the learning outcomes of embedding this art theme with an educational activity?

With this activity, learners will be able to discover Antiquity through the sculptures and painter’s techniques and vision. The activities are set so that learners can learn the power of all important techniques used during this artistic and cultural movement. They will also be able to delve more into specific sculptures and paintings and watch video explanations of some of the most influential artworks.

How to do it : strategies, tools, and techniques.

Learners will take an active and an inactive participation throughout their learning. They can observe the suggested artworks, they can read the information about the artwork, which will allow them to expand their artistic knowledge and they can use the possible education exploitations as guidance for exercises, reflection on the topic and the artwork itself.

Artworks

Artwork #1 Augustus of Prima Porta

- Its position-relation to the theme: The artist is unknown. The work dates back to the 1st century. It is a full-length portrait statue of Augustus Caesar. He is the first emperor of the Roman Empire. The statue was discovered in 1863 during archaeological excavations at the Villa of Livia. The villa was owned by Augustus’ third and final wife, Livia Drusilla in Prima Porta.

- Short description: The statue is a portrait of Augustus as an orator and general. But it also communicates a good deal about the emperors’ power and ideology. In this portrait Augustus shows himself as a great military victor. It was made out of marble, it is 2.08 meters high and weights around 1000 kilograms.

- Location and European dimension: The statue is now displayed in the Braccio Nuovo (New Arm) of the Vatican Museums.

- Possible educational exploitation: The statue is very unique and important. We would like to challenge the learner to discover more information about the details on the clothing of the statue and the meaning of the small figure next to it. Some additional information about this statue can be found in the Virtual Exhibitions section of this project.

Artwork #2 Peplos Kore

- Its position-relation to the theme: The artist is unknown. The work dates back around to 530 BC. It is a statue of a girl. It is a kore statue. Kore is the modern term given for a free-standing ancient Greek sculpture of the Archaic period. It depicts female figures of a young age. The statue was found in 3 pieces.

- Short description: A peplos is a type of dress worn by women in Greece c.500 BCE. The statue has bore holes on the head and shoulders. Someone says that this statue type does not depict mortal girls but goddesses. The statue on the face has a smile. It is called “archaic smile”. It is similar to many Greek statues from the Archaic period. The statue is 118 cm-high. It is in white marble. The marble is from Paros.

- Location and European dimension: The statue is now displayed at the Archaic Acropolis Gallery in the Acropolis Museum in Athens.

- Possible educational exploitation: Adult educators are advised to look into the meaning of the bore holed on the head and the shoulders. Furthermore, it would be very interesting for them to understand what an “archaic smile” means. This suggests exploration of the Virtual Exhibitions of this project and some further reading. Hereby a link to one resource to help you start exploring.

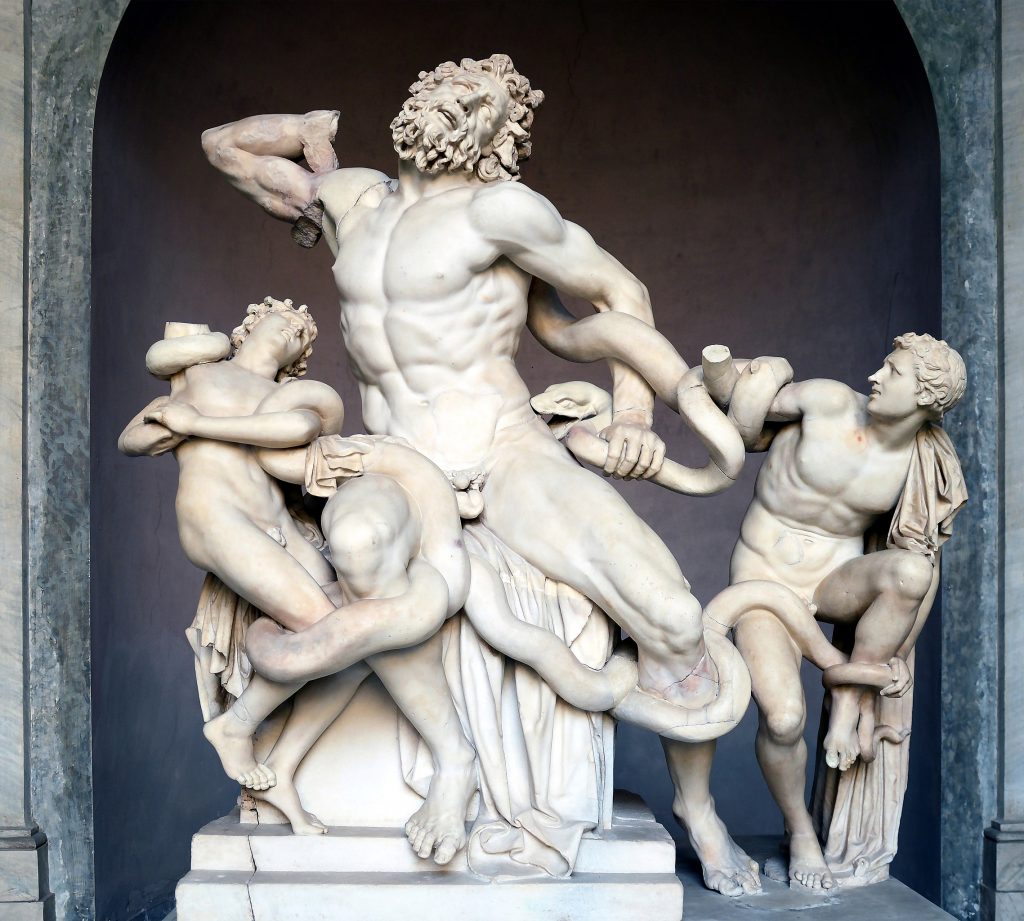

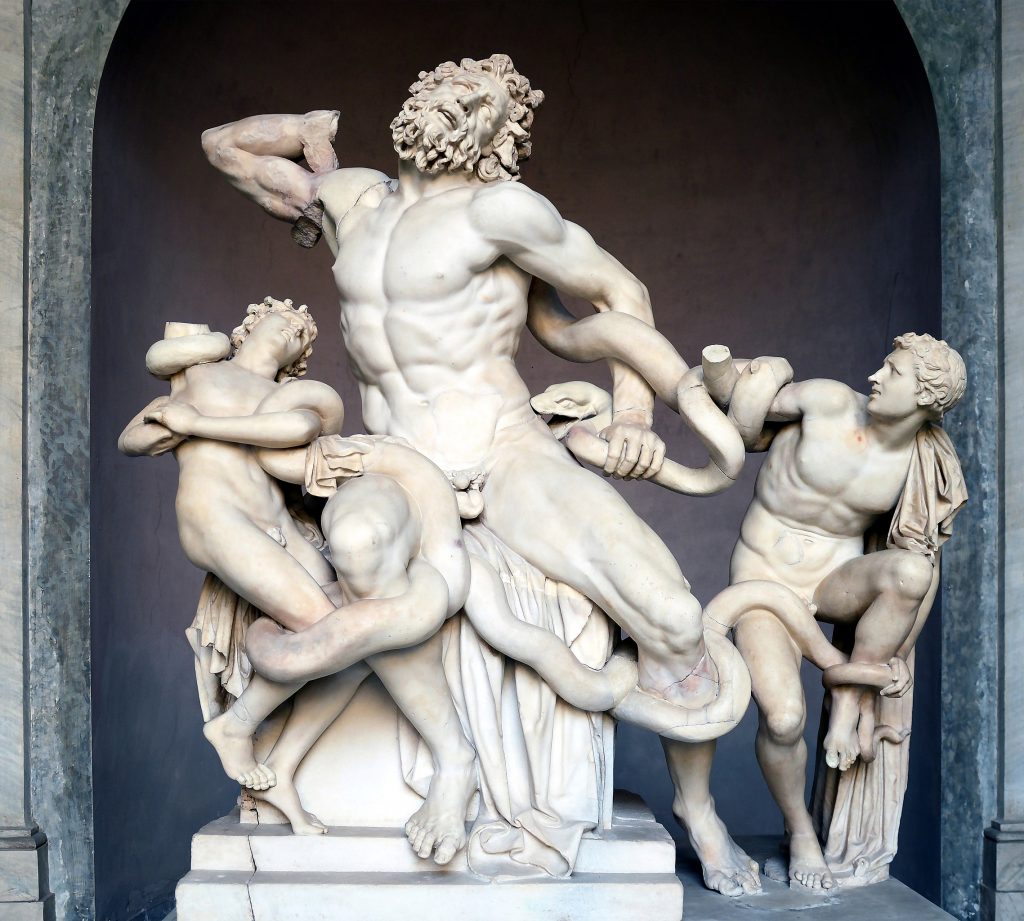

Artwork #3 Laocoön and His Sons

- Its position-relation to the theme: Laocoön and His Sons is a marble sculpture from the Hellenistic Period (323 BCE – 31 CE). The story of Laocoön comes from the Greek Epic Cycle on the Trojan Wars. There are several stories. In every version, gods send the snakes to punish Laocoön. According to Pliny the Elder, Laocoön was a priest of Apollo in the city of Troy. Laocoön warned his fellow about the wooden horse. To be wary. So, Poseidon and Athena, favouring the Greeks, send sea-serpents for killing him.

- Short description: It is also called the Laocoön Group. Figures are near life-size, and the group is a little over 2 m. Seven interlocking pieces of white marble compose the statue. It shows Laocoön and his sons Antiphantes and Thymbraeus attacked by sea serpents. In true Hellenistic fashion the statue showcases an interest in the realistic depiction of movement.

- Location and European dimension: The statue is now displayed at the Vatican Museums, at the Vatican City.

- Possible educational exploitation: There are many debates about the statue. We are not sure if it is an original work or a copy of an earlier sculpture. We ask you to have a look at the materials at the virtual exhibitions and check online, to see whether you can find out whether this is an original work or not.

Artwork #4 Venus de Milo, Alexandros of Antioch

- Its position-relation to the theme: The work dates back between 150 and 125 BC. The Venus de Milo is an ancient Greek sculpture. It represents one of the most famous sculptures of the Hellenistic period. The Hellenistic period ends with the conquest of the Greek world by the Romans.

- Short description: It is a statue of Parian marble. It represents a female figure. The statue is half-clothed with a bare torso. Her chest is naked. The reason behind the arms being missing in the first place is unknown.

- Location and European dimension: The statue is now displayed at the Louvre Museum in Paris.

- Possible educational exploitation: Without arms, it is unclear what the statue originally looked like. We ask the adult learners, after learning more about the antiquity period to think of the possible arms and their positions. Critics think the statue represent Venus. Venus is the Roman goddess of love, beauty, passion. She is the counterpart of the Greek goddess Aphrodite. Others suggest that she could be Amphitrite. Amphitrite is the goddess of the sea.

Artwork #5 Ruins of the Parthenon, Sanford Robinson Gifford, 1880

- Its position-relation to the theme: Sanford Robinson Gifford is the author of this painting. He is an American painter, who lived between 1823 and 1880. The painting was made after Sanford Robinson Gifford returned from the Acropolis in 1869. The artist considered it his last important painting. This was the crowing of his career. He hoped it will be acquired by an American museum.

- Short description: Gifford’s landscapes are known for their emphasis on light and soft atmospheric effects. The image doesn’t contain symbolism. He painted using a mixture of dark and light brown colours using oil paint. It has a timeless, monumental quality.

- Location and European dimension: The painting is located in the Washington, US

- Possible educational exploitation: Some critics refer to this painting as: “not a picture of a building, but a picture of a day.” Reflect on this phrase. Why do you think they mean with this saying? Would you also relate to their opinion? Why / why not?

Artwork #6 Winged Victory of Samothrace, or the Nike of Samothrace

- Its position-relation to the theme: The Winged Victory of Samothrace, or the Nike of Samothrace,[2] is a votive monument originally found on the island of Samothrace, north of the Aegean Sea. It is a masterpiece of Greek sculpture from the Hellenistic era, dating from the beginning of the 2nd century BCE. It is composed of a statue representing the goddess Niké (Victory), whose head and arms are missing, and its base in the shape of a ship’s bow.

- Short description: The statue, in white Parian marble, depicts a winged woman, the goddess of Victory (Nikè), alighting on the bow of a warship. The Nike is dressed in a long tunic (chitôn) in a very fine fabric, with a folded flap and belted under the chest. It was attached to the shoulders by two thin straps (the restoration is not accurate). The lower body is partially covered by a thick mantle (himation) rolled up at the waist and untie when uncovering the entire left leg; one end slides between the legs to the ground, and the other, much shorter, flies freely in the back. The sculptor has multiplied the effects of draperies, between places where the fabric is plated against the body by revealing its shapes, especially on the belly, and those where it accumulates in folds deeply hollowed out casting a strong shadow, as between the legs. This extreme virtuosity concerns the left side and front of the statue. On the right side, the layout of the drapery is reduced to the main lines of the clothes, in a much less elaborate work. With her elbow bent, the goddess made her hand a victorious gesture of salvation: this hand with outstretched fingers held nothing (neither trumpet nor crown).

- Location and European dimension: The sanctuary of the Great Gods of Samothrace is located in a very narrow river valley of the Samothrace temple complex. The Victory was situated above the theatre at No. 9.

- Possible educational exploitation: We ask the learners to look at the meaning of the boat and the base. What was the statue made of? What were the boat and base made of? Are the dimensions of this artwork similar to the previously shown statues? Why do you think this is / is not the case?

Artwork #7 Severan Tondo

- Its position-relation to the theme: The Severan Tondo or Berlin Tondo from circa 200 AD, is one of the few preserved examples of panel painting from Classical Antiquity, depicting the first two generations of the imperial Severan dynasty, whose members ruled the Roman Empire in the late 2nd and early 3rd centuries. It depicts the Roman emperor Septimius Severus (r. 193–211) with his wife, the augusta Julia Domna, and their two sons and co-augusti Caracalla (r. 198–217) and Geta (r. 209–211). The face of one of the two brothers has been deliberately erased, very likely as part of damnatio memoriae.

- Short description: The work is a tempera, or egg-based painting, on a circular wooden panel, or tondo. It depicts the Imperial family wearing sumptuous ceremonial garments. Septimius Severus and his sons are also holding sceptres and wearing gold wreaths decorated with precious stones. Scholars believe that the darker skin tone of Severus in the tondo probably reflects his gender more than his ethnic background. Julia Domna has her distinctive hairstyle, crimped into parallel locks, possibly a style from her home in Syria, and perhaps a wig. Although it is commonly assumed that Julia Domna introduced the custom of wearing wigs into Roman society, evidence points to a predecessor introducing use of wigs in portraiture. One son’s face has been obliterated in a deliberate act of iconoclasm, and the vacant space smeared with excrement. Most scholars believe it is Geta whose face has been removed, probably after his murder by Caracalla’s Praetorian Guard and the ensuing damnatio memoriae. However, it is also possible that Geta (as the younger son) is the smaller boy, and it is Caracalla’s face which was eradicated, perhaps as a compensatory retaliation for Caracalla’s mass execution of young Alexandrian men in the year 215.

- Location and European dimension: The history of the painting after its creation is not known until the Antikensammlung Berlin acquired it in 1932 from an art dealer in Paris. It is in the Altes Museum, one of the Berlin State Museums.

- Possible educational exploitation: An in-depth analysis in colors and colors theory could be a good exercise for this painting, especially when knowing the colour palettes typically used in this period.

Artwork #8 Pair of Centaurs Fighting Cats of Prey from Hadrian’s Villa, mosaic, c. 130 C.E.

- Its position-relation to the theme: Hadrian was the greatest patron of the arts. His imperial villa at Tibur was adorned with the very best of what the Roman empire had to offer in terms of works of art and building materials. Hundreds of statues, reliefs, architectural marbles and other decorations were found in the villa. Many of them have been lost, others are in Museums and private collections around the world.

Of particular interest is the central panel (emblema) of a large mosaic depicting a pair of centaurs (mythological creatures with the head, arms, and torso of a man and the body and legs of a horse) fighting wild cats. It is one of the most significant Roman mosaics. Mosaics were used throughout the complex but polychrome mosaics were only used in the noble buildings.

- Short description: The dramatic scene depicts a centaur casting a rock at the tiger who has slain his female companion. The female centaur lies dead, bloodied by the raking claws of the beast. The mosaic is made of thousands of small, closely set tesserae (1-2 millimiters) called opus vermiculatum. The mosaic dates back to 120-130AD and was created by numerous natural stones that varied in color. The artwork remains as a floor decoration in the dining room of the main palace within Emperor Hadrian’s extensive villa complex.

- Location and European dimension: The statue is located in the Altes Museum, Berlin, Germany

- Possible educational exploitation: Have a look at this video: https://smarthistory.org/pair-of-centaurs-fighting-cats-of-prey-from-hadrians-villa/

Can you find another example of an artwork or mosaic, created during the antiquity (the Hellenistic Age) period, that was displayed in another emperor’s home? Are the colours used in it similar to the one of the Pair of Centaurs Fighting Cats of Prey from Hadrian’s Villa? Why do you think this is (not) the case?

Optional – Have you worked with mosaics previously? Perhaps this can be a great experience and experiment for your class to give this technique a try.

Artwork #9 Julius Caesar

- Its position-relation to the theme: Marble head from a statue, probably of Julius Caesar. The head has been burnt and is badly damaged, with the proper right side and back of the head missing.

Excavated/Findspot: Sanctuary of Athena Polias; Materials: marble

- Short description: Full name Caius Julius Caesar, always known in modern timnes as Julius Caesar, and the subject of the play by Shakespeare. Best known for his role in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire. He conquered Gaul (and wrote a book about it) and was a member of the First Triumvirate, but after the collapse of that political alliance became an enemy of Pompey the Great’s (q.v.) and crossed the Rubicon to march on Rome as part of the struggle. He attained multiple Consulships and was named dictator perpetuus, a move which sparked the jealousy of C. Cassius Longinus (q.v.) and concern of M. Junius Brutus (q.v.). These two men headed the plot which led to the assasination of Julius Caesar on March 15, 44 BC.

- Location and European dimension: The sculpture is located at the British Museum. It is 39.37cm high.

- Possible educational exploitation: How was Julius Caesar portrayed in the play by Shakespeare? Is there a more recent restoration of this statue? How is it different from the original? Can you think of other leaders of the past that have been portrayed in a play? Who are they?

Artwork #10 Charioteer of Delphi

- Its position-relation to the theme: The Charioteer of Delphi, also known as Heniokhos (the rein-holder), is a statue surviving from Ancient Greece, and an example of ancient bronze sculpture. The life-size (1.8m) statue of a chariot driver was found in 1896 at the Sanctuary of Apollo in Delphi.

- Short description: It was originally part of a larger group of statuary, including the chariot, at least four horses and possibly two grooms. Some fragments of the horses were found with the statue. The masterpiece has been associated with the sculptor Pythagoras of Samos who lived and worked in Sicily, as well as with the sculptor Calamis. The Sicilian cities were very wealthy compared with most of the cities of mainland Greece and their rulers could afford the most magnificent offerings to the gods, also the best horses and drivers. It is unlikely, however, the statue itself comes from Sicily. The name of the sculptor is unknown, but for stylistic reasons it is believed that the statue was cast in Athens. It has certain similarities of detail to the statue known as the Piraeus Apollo, which is known to be of Athenian origin. An inscription on the limestone base of the statue shows that it was dedicated by Polyzalus.

- Location and European dimension: This statue is now located in the Delphi Archaeological Museum in Greece.

- Possible educational exploitation: The atmosphere and feeling coming off from the statue are very special. It can be interesting to analyse it comparing it to other statues to see how differently carved facial expressions can make such a big difference.

Practical activities

Activity 1: Sketching of a statue (respective of time)

Aims

To help learners discover how the artist in the antiquity period created the statues. It is important to observe the body posture and gestures portrayed.

Materials

- Sketchbook

- Pen

- Rubber

If the learners are artists, then they can use their painting materials with an easel.

- A printer or projector

Preparatory stage for educators/mediators

Show the learners a number of different antique statues. This will help the learners to understand what we are trying to achieve.

Development

Ask your learners to select a statue, that they will have to sketch with the exact same view or perspective. Once they have selected their statue, set the schedule. One sketch should ideally be done in 5 minutes, one in 15 minutes, one in 45 minutes and one they can work on for as long as time permits

They can create 4 versions of the same sketch in 4 different time-frames. This will give them a perspective of time, to recreate an artwork, in the form of a statue, rather than a painting or a sketch. Think with your classroom of the role of time, how it affects quality, detail, colours, and techniques.

Activity 2 : Visit a museum online (could requires budget)

Name of the activity

Visit a museum online, for example the National Archaeological Museum of Athens (online)

Aims

For learners to discover the antiquity period, specifics about paintings, techniques and more.

Materials

Access to a computer with an online connection.

Budget for an online exhibition ticket (note: some museums have free virtual exhibitions). It can also be that the educator purchases one ticket and showcases the virtual exhibition in class, if this is allowed.

Preparatory stage for educators/mediators

The museum visit is self-guided. However, the educator can get in touch with the organisation or visit themselves alone first, to be able to focus on specific artworks with the class rather than asking learners to explore and follow everything by themselves.

Development

Learners can explore more about specific statues and more through this website, and then the educator can create a quiz that they can take at the end to evaluate their knowledge.

Digital Exhibitions – namuseum

Acropolis Museum, Athens, Grèce — Google Arts & Culture