Introduction

Art is a beautiful and curious thing, for when it is used to serve the purpose of creating change, unity, and power through resistance, it has great strength in connecting people with a common message.

In this pedagogical dossier, we will first introduce you to the origins of the movement, providing a brief historical and cultural context to its rise. Then, we will go into details about the specifics of the movement, based on artists, colours, shapes, brushstrokes, perspective and more. Lastly, we will introduce you to 10 artworks that were created during the period and provide you with 2 practical example of activities that can be implemented for an art workshop based on Resistance and Protest art.

To summarize, in this dossier, you will:

- Learn the origins of the movement,

- Discover some of its key figures and influencers,

- Explore the characteristics of the artwork techniques,

- And more!

The theme

Background of the movement

Protest, struggle, and political activism are powerful tools of resistance. Power through mobilization of people can create measurable positive change in our world. In particular, using art as a nonviolent form of protest can carry immense meaning and strength, connecting people through their resistance. It can turn negative and fear-filled topics into something to rally behind. Protest Art, also referred to as Resistance art, is related to the creative works produced by activists and social movements. Protest art helps arouse base emotions in their audiences, and in return may increase the climate of tension and create new opportunities to dissent.

“Protest art itself doesn’t create change, but it aims to embolden and galvanize enough people across socioeconomic backgrounds to mobilize for a cause. In order to do so successfully, a call to arms should be immediate, brazen, and most importantly, have soul”

(Lanks, 2016).

Different forms of art can link people in different ways. The power of music by writing and singing songs of freedom has developed into a tradition at the heart of many movements. Music has been recognised as one uniting force that helped create and strengthen a common consciousness (Eprile, 2017). Visual art as protest is another way that art is used as a means of resistance in order to create change for the better. Art is a critical tool that is always being used to influence a populaces thoughts and behaviours, if it this was not the case, government funded propaganda would not exist, neither would the destruction of art or the burning of books.

Resistance art is art used as a way of showing their opposition to powerholders. This includes art that opposed such powers as the German Nazi party, as well as that opposed to apartheid in South Africa. The Soweto uprising marked the beginning of social change in South Africa. Resistance art grew out of the Black Consciousness Movement, a grass-roots anti-Apartheid movement that emerged in the 1960s lead by the charismatic activist Steve Biko. Much of the art was public, taking the form of murals, banners, posters, t-shirts and graffiti with political messages that were confrontational and focused on the realities of life in a segregated South Africa. Willie Bester is one of South Africa’s most well-known artists who originally began as a resistance artist. Using materials assembled from garbage, Bester builds up surfaces into relief and then paints the surface with oil paint. His works commented on important black South African figures and aspects important to his community. South African resistance artists do not exclusively deal with race nor do they have to be from the townships. Bester currently lives in Kuilsrivier, South Africa.

Another artist, Jane Alexander, has dealt with the atrocities of apartheid from a white perspective. Her resistance art deals with the unhealthy society that continues in post-apartheid South Africa.

Artists such as John Trumbull, Emory Douglas, Martha Rosler, Keith Haring, Judy Chicago were famous American artists during the period.

John Trumbull (June 6, 1756 – November 10, 1843) was an American artist of the early independence period, notable for his historical paintings of the American Revolutionary War, of which he was a veteran. He has been called “The Painter of the Revolution”

The painting Surrender of Lord Cornwallis by John Trumbull is on display in the Rotunda of the US Capitol. The subject of this painting is the surrender of the British army at Yorktown, Virginia, in 1781, which ended the last major campaign of the Revolutionary War.

Douglas served as the revolutionary artist and minister of culture for the Panthers, and was in charge of creating images (largely disseminated through its official newspaper) that established a visual record of the party’s platform.

Emory Douglas, We Shall Survive Without a Doubt (1971) is a courtesy of Black Lives Matter and can be seen on Black Lives Matter website.

There had always been a psychological response that did transcend the Black Panther Party in the African American community and it became a national and international symbol. It has always been a part of the people’s cultural identity in relationship to how they thought about injustice. The pigs became a psychological symbol of resistance.

Emory Douglas’s illustration of police officers as pigs for the Black Panther Party is a courtesy of Flickr creative commons. The artwork can be seen here.

In Europe artist such as Eugène Delacroix, Henri Rousseau, Francesco Goya, Salvador Dali and Pablo Picasso, expressively began documenting their vision on the war. In his work, Goya sought to commemorate Spanish resistance to Napoleon’s armies during the occupation of 1808 in the Peninsular War. Goya painted The Third of May 1808, which is considered as an inspirational piece to Gerald Holtom peace sign and a number of later major paintings, including a series by Édouard Manet, and Pablo Picasso’s Massacre in Korea and Guernica. It is not known whether he had personally witnessed either the rebellion or the reprisals, despite many later attempts to place him at the events of either day. The Second and Third of May 1808 are thought to have been intended as parts of a larger series. At first the painting met with mixed reactions from art critics and historians.

Artists had previously tended to depict war in the high style of history painting, and Goya’s unheroic description was unusual for the time. According to some early critical opinion the painting was flawed technically: the perspective is flat, or the victims and executioners are standing too close together to be realistic. Although these observations may be strictly correct, the writer Richard Schickel argues that Goya was not striving for academic propriety but rather to strengthen the overall impact of the piece. Pictorial artifice gives way to the epic portrayal of unvarnished brutality. The painting is structurally and thematically tied to traditions of martyrdom in Christian art, as exemplified in the dramatic use of chiaroscuro, and the appeal to life juxtaposed with the inevitability of imminent execution.

Even the contemporary Romantic painters—who were also intrigued with subjects of injustice, war, and death—composed their paintings with greater attention to the conventions of beauty, as is evident in Théodore Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa (1818–1819) and Eugène Delacroix’s 1830 painting Liberty Leading the People.

Henri Rousseau’s La Guerre also represents the effects of the war.

The horse in the painting contrasts with that of La Carriole du Père Junier: black, wild and bristling, it represents the brutal force of war. On her back, the armed, ugly and savage woman suggests that war brings primitiveness. The bottom of the painting shows the effects of war: corpses that are the food of crows. The bare trees and broken branches create a landscape of desolation and allude to death, even if the pink of the clouds and the blue of the sky do not reveal the drama of the scene. The composition is pyramidal, with the corpses at the base, and the horse and the woman above.

Pablo Picasso was inspired by Goya’s work. Guernica is a large 1937 oil painting on canvas by Pablo Picasso. It is one of his best-known works, regarded by many art critics as the most moving and powerful anti-war painting in history. It is exhibited in the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid.

Picasso painted Guernica at his home in Paris in response to the 26 April 1937 bombing of Guernica, a Basque Country town in northern Spain which was bombed by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy at the request of the Spanish Nationalists. Over the years, Guernica has since become a universal and powerful symbol warning humanity against the suffering and devastation of war.

During the same time-frame Salvador Dali painted “The Face of War”. It was painted during a brief period when the artist lived in California. The trauma and the view of war had often served as inspiration for Dalí’s work. He sometimes believed his artistic vision to be premonitions of war. This work was painted between the end of the Spanish Civil War and the beginning of the Second World War.

The artwork of Salvador Dalí: The Face of War (1940, oil on Canvas, 64cm x 79cm) is under copyright and can be seen at the Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam (Netherlands).

The painting depicts a disembodied face hovering against a barren desert landscape. The face is withered like that of a corpse and wears an expression of misery. In its mouth and eye sockets, there are identical faces. In their mouths and eyes, there are more identical faces in a process implied to be infinite. Swarming around the large face are biting serpents. In the lower right corner is a handprint that Dalí insisted was left by his own hand.

Historical and societal context of the movement

Social movements are often defined by their message but remembered by their art and the imagery they used. Whether the art was movement-based (art that emerges from within social movement groups themselves) or movement supportive (art by professional artists that use their practice as a way to support social movements, and while can be directly linked to the movement, are not part of the movement organizations), the use of artistic expression is integral to social movements, especially in protest art, as they are utilized in such a way that allows an easy expression of complex ideas such as cultural expression, social/class

struggle, and identity, to be communicated through its medium because rather than passing around complicated theory books for the unaware layman to read, (movement-based) protest art is traditionally easy to distribute, consume and understand – its message is loud and clear and does not allow for barriers like literacy and level of education to halt its ability to have its message be effectively communicated and understood.

Looking to two social movements over history, the ones that stand out are the African American Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and the current (2014 – 2020/present) Black Lives Matter Movement. The African American Civil Rights Movement is a social movement that easily has some of the most memorable motifs in the modern [western] collective consciousness. From Martin Luther King’s iconic “I have a dream” speech at the March on Washington for Jobs protest, to the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committees iconic image (Photograph by Danny Lyon, ‘SNCC NOW’ Poster, 1964, 55.9 x 35.6 cm) of the student protesters with their eyes closed and arms raised in prayer, symbolizing Black Power.

Art is a common thread underlying countless resistance movements and protests that have united people and brought about positive societal change. Whether it be through music, visual art, dance, drama, or any other art form, art has a way of connecting with our human emotions and uniting us through hope and power. In this way, art has the power to turn Doom into Bloom and provide a platform for people to stand together, not alone.

In the past fifty-to-hundred years some movements have had a greater cultural impact on the society. Resistance art, ongoing Activist art, Pop art and the women’s movement, which re-emerged in the 1960s and has grown in multifaceted ways into the present. The tremendous impacts of feminism on everyday life include, but extend far beyond, changes in laws, regulations, and political institutions. The texture of the life of every single person living in the United States has been changed by the new feminism.

Characteristics of the movement

There are several characteristics that can help a viewer identify the traits. Here are some of the most common ones:

Symbols

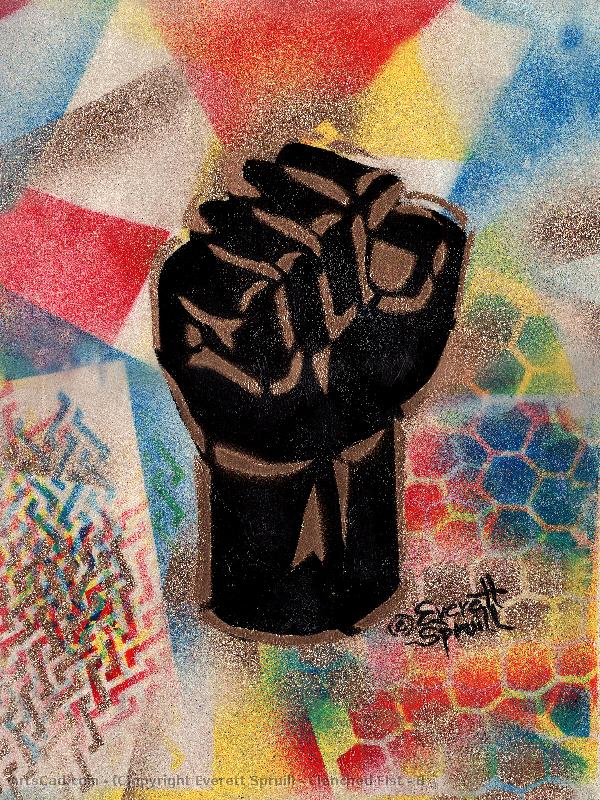

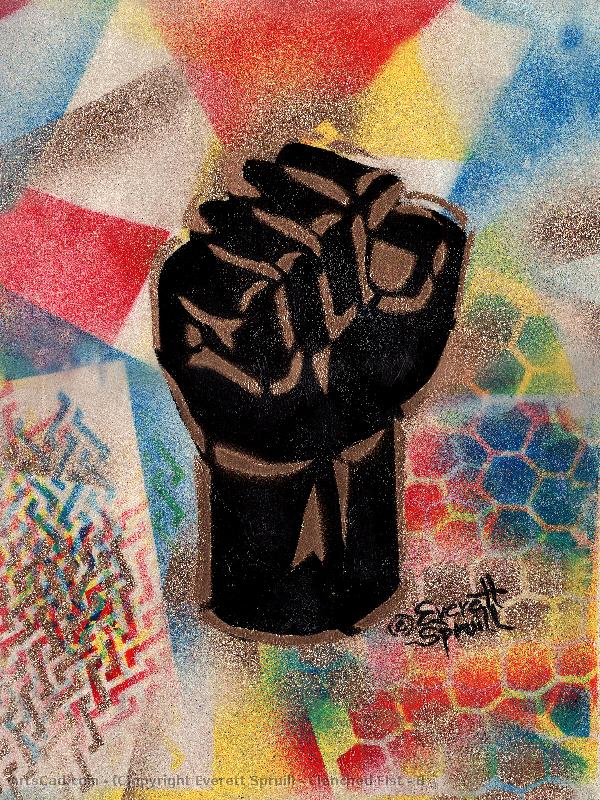

The clenched fist is a common recurring theme in protest and resistance art and has been used already since during the Mexican Revolution, the American students’ protest against the Vietnam war, the Black Panther Party, as well as French students during their socialist rebellion in 1832 against the monarchy.

The Mexican American Chicano movement saw murals as a form of protest against the injustices harming their marginalized population. At the end of the Mexican Revolution the government commissioned artists to create art that could educate the mostly illiterate masses about Mexican history. Celebrating the Mexican people’s potential to craft the nation’s history was a key theme in Mexican muralism, a movement led by Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, and José Clemente Orozco—known as Los tres grandes. Between the 1920s and 1950s, they cultivated a style that defined Mexican identity following the Revolution.

Los tres grandes (the three greats), as they are known, were important models not only as major modern artists but also as political activists who rooted their muralism in support for the struggles of the poorest, most exploited members of their communities.

The Mexican Revolution was a watershed moment in the twentieth century because it marked a true break from the past, ushering in a more egalitarian age. With its grand scale, innovative iconography, and socially relevant message, Mexican muralism remains a notable compliment to the Revolution.

The muralists developed an iconography featuring atypical, non-European heroes from the nation’s illustrious past, present, and future—Aztec warriors battling the Spanish, humble peasants fighting in the Revolution, common laborers of Mexico City, and the mixed-race people who will forge the next great epoch, like in Siqueiros’ UNAM mural. Los tres grandes crafted epic murals on the walls of highly visible, public buildings using techniques like fresco, encaustic, mosaic, and sculpture-painting.

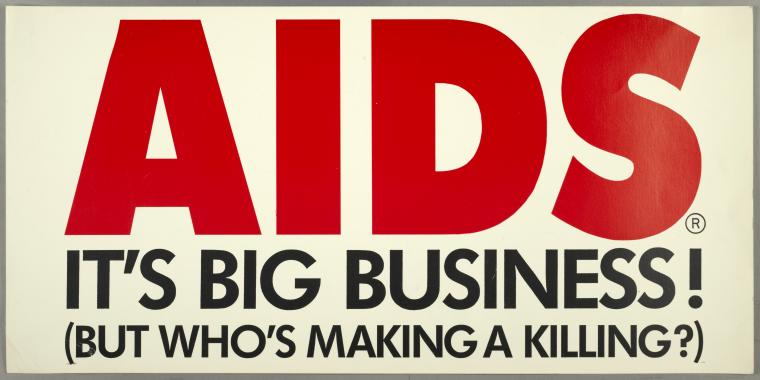

Furthermore, in a time of crisis, art was used as a very visual way to act against AIDS. To combat the harmful cultural construction around “contaminated blood”, the social movement groups of the late 1980s and 1990s, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, or ACT UP created posters and graphics to try and attract people’s attention and encourage conversation about the uncomfortable social and cultural truths surrounding AIDS.

Many of the ACT UP designs incorporated text and images; this poster is one of a few that communicated a message using text alone. The poster was made for an action at the New York Stock Exchange in September 1989 (two and half years after ACT UP’s first protest, which also took place on Wall Street). All of the Wall Street protests (a second took place a year after the first) were concerned with the huge profits that the pharmaceutical company Burroughs Wellcome was making from the AIDS drug AZT. The company had received a patent ensuring that no other company could sell the drug for seventeen years. The company argued that it was justified in charging an exorbitant price for the drug considering it had spent a significant sum of money on its development. ACT UP countered that taxpayers had footed the bill through grants and tax credits. In the September 1989 action, activists requested that AZT be provided free of charge to anyone who needed the drug.

Colours

Panther Party Members donning all black outfits with berets and large Afros and the Hippie counter culture at the time wearing technicolour outfits and carrying bright signage protesting the Vietnam War and advocating for ‘peace, love, and equal rights,’ it is a movement that even now had strong an effective motive that still influence culture today which can be seen in the current #BlackLivesMatter Movement.

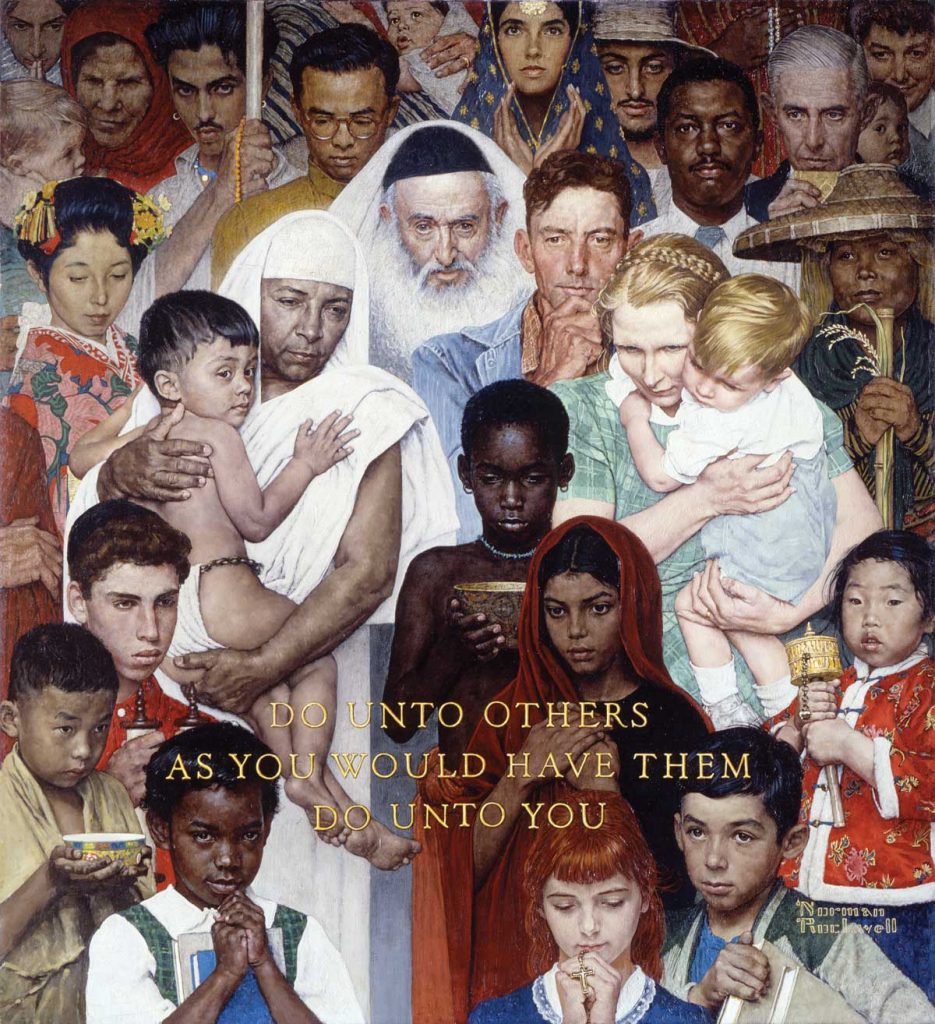

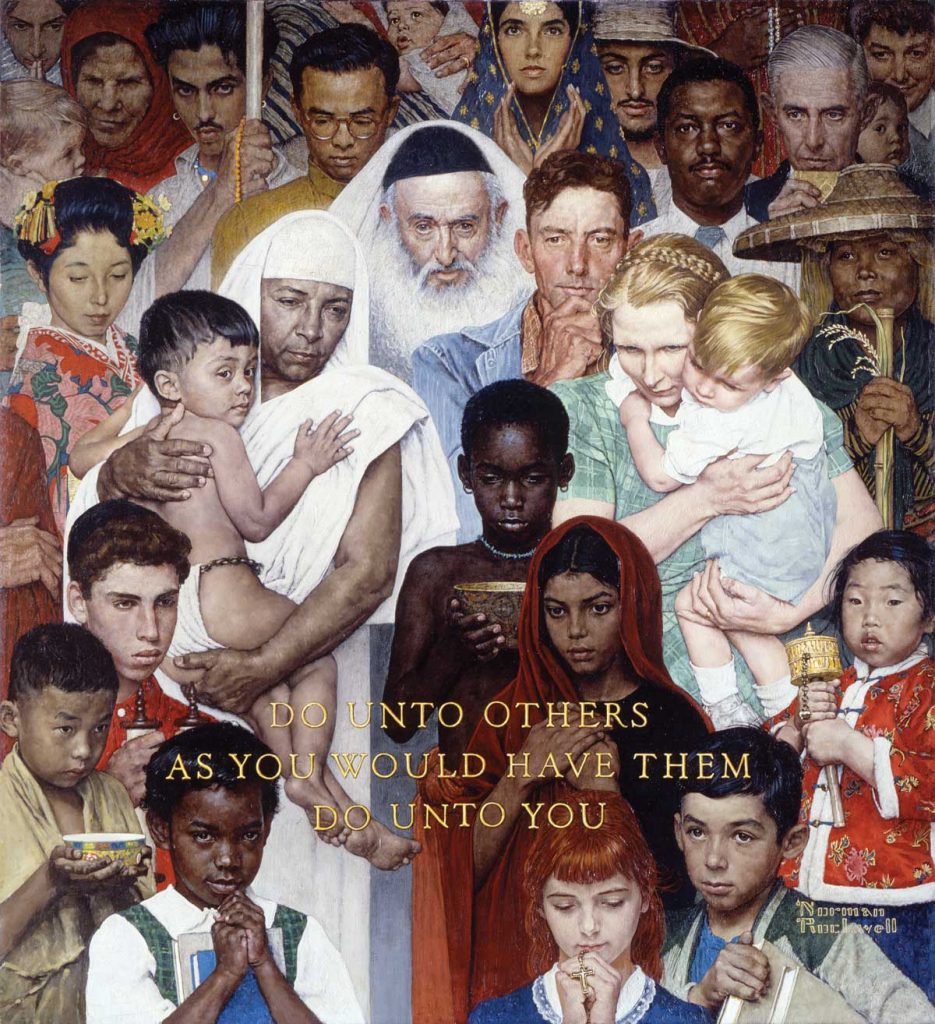

The use of colour, not only observed in outfits but also in colourful works can be seen not only in painter’s work, but also in illustrator’s work. The works ‘The Golden Rule’ (1961) and ‘The Problem We All Live With’ (1963) by Norman Rockwell, as he was already a well-known and respected white illustrator in the art community his art falls into the movement supportive category of protest art. ‘Golden Rule ’ is a painting that features a collage of people of different ethnicities and cultures and a reference to the bible verse Mathew 7:12. Out of all the people features in the painting the most notably a small black girl in a school uniform with her eyes directly meeting the viewer of the painting – the girl is a direct reference to Ruby Bridges, a 6 year old African American girl that was the first to attend an all-white elementary school in the south, she was escorted to class by her mother and U.S. marshals to ensure her safety due to angry protesting mobs on 14 November, 1960, and every other day that year.

Story illustration for The Saturday Evening Post, April 1, 1961 (source : UN.org)

Relevance in the modern era

The concept of ‘art being a weapon’ is still relevant in the modern era. It simply has just been re-contextualized by the emergence of modern technologies such as social media. Looking towards the Black Lives Matter movement which emerged in 2013 in response to the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s murderer, George Zimmerman and then in 2014 gained global attention when protests sparked in Ferguson, Missouri in response to the murder of Mike Brown by Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson (who was also exonerated of criminal wrongdoing in court) and images and videos of the horrifying amounts of police brutality protesters were being documented and shared in real time on social media sites such as Twitter, Instagram and Facebook.

Red Paint was added by unknown protester(s) during #BlackLivesMatter Protests on the 29th May.

Pedagogical approach

Why is this theme relevant to adult learners?

Protest Art is one of the most recognizable art movements of the past century. Through participation in an activist art program, students can develop skills for critical thinking, leadership, community engagement, and communication. While creating works of activist art, they can engage in three learning and teaching processes that were key to the development of these skills:

Connecting – Students think about the injustices they intend to address through their art, they consider why these injustices exist and how they could be changed. They identify relationships and connections of cause and effect, actively constructing an understanding of community relationships and civic leadership.

Questioning – Once students form ideas about their topics, they begin a long process of critical thinking: How can we impact this injustice? Who is my audience? How do I want them to think about the topic? How can I communicate my ideas effectively? Does my art work as I intended? Students begin to see the legitimacy of their own insight for challenging the status quo, and they begin to understand their power as active creators of society capable of initiating change.

Translating – Representing an idea through art required a shift from verbal to visual language. By translating their ideas into art, students re-frame their ideas literally, metaphorically, ironically, dialogically (as an interaction with the audience), or through a mixed approach. Students learn to see art as a way of “teaching” the audience.

They sought to present their ideas with a balance between message and aesthetics, and develop communication skills in the process. These outcomes are in line with doctorial study on the topic by M. Dewhurst in 2009.

What are the learning outcomes of embedding this art theme with an educational activity?

With this activity, learners will be able to discover the topic through the painter’s tools and eyes. Indeed, the activities are set so that learners can learn the power of activist art, music and words, reflecting on how it can influence artistic views. They will also be able to delve more into specific paintings and watch video explanations of some of the most influential works.

How to do it: strategies, tools, and techniques.

Learners will take both an active and inactive participation in their own learning. Indeed, using their painting skills, critical thinking and listening skills they will be able to develop their knowledge of historical and protest art, and discuss with the class, then learn from other experts in the fields of art history.

Artworks

Artwork #1 Liberty Leading the People, Eugene Delacroix, 1830

- Its position-relation to the theme: Liberty Leading the People (French: La Liberté guidant le peuple [la libɛʁte ɡidɑ̃ lə pœpl]) is a painting by Eugène Delacroix commemorating the July Revolution of 1830, which toppled King Charles X of France.

- Short description: A woman of the people with a Phrygian cap personifying the concept of Liberty leads a varied group of people forward over a barricade and the bodies of the fallen, holding the flag of the French Revolution – the tricolour, which again became France’s national flag after these events – in one hand and brandishing a bayonetted musket with the other. The figure of Liberty is also viewed as a symbol of France and the French Republic known as Marianne. The painting is sometimes wrongly thought to depict the French Revolution of 1789.

- Location and European dimension: Liberty Leading the People is exhibited in the Louvre in Paris.

- Possible educational exploitation: This painting was quite controversial when it was first made public, it can be interesting for learners to inquire as to the different reaction it created, why they were negative based on societal observation and what and why some people liked it.

Artwork #2 Emory Douglas, We Shall Survive Without a Doubt (1971)

Emory Douglas, We Shall Survive Without a Doubt (1971) is a courtesy of Black Lives Matter and can be seen on Black Lives Matter website.

- Its position-relation to the theme: “Revolutionary art begins with the program that Huey P. Newton instituted with the Black Panther Party,” graphic designer and Black Panther Minister of Culture Emory Douglas wrote in The Black Panther newspaper in 1970. “Revolutionary art, like the Party, is for the whole community and deals with all its problems. It gives the people the correct picture of our struggle whereas the revolutionary ideology gives the people the correct political understanding of our struggle.” Pictured here is Douglas’s back cover poster for the February 17, 1970, issue of the paper, which he also designed. (Caption reads: “We shall survive. Without a doubt.”) “Deploring imperialism, capitalism and police brutality, Douglas depicted police, politicians and bankers as pigs and rats,” the curators of Soul of a Nation write. “Heroic Black women fight actual rats in substandard housing. Valiant workers are shown as revolutionary soldiers. A smiling child holds his head high, wearing sunglasses whose lenses are photographs of the free breakfast program that the Party implemented to feed children of poor and working families.

- Short description: Headed with the phrase, “We shall survive. Without a doubt,” the image depicts a brilliantly smiling young African-American child wearing glasses and, in place of lenses, are images of the young being educated—we assume in Black Panther community schools. Atop his head is a floppy, zoot-style hat, emanating red rays quoted directly from Chinese revolutionaries…Typically in the Chinese source images, one would see the red rays emanating from behind Mao, the leader, but in his works, Douglas links them to the children, granting them [as the] agents of change. The artwork location is unknown.

- Possible educational exploitation: Analyse the meaning on the text of this artwork. What is Douglas trying to tell the viewer? How is this related to the images of the children? Reflect on the years and era, timeframe that this artwork was completed in.

Artwork #3 Salvador Dalí, The Face of War, 1940

The artwork of Salvador Dalí: The Face of War (1940, oil on Canvas, 64cm x 79cm) is under copyright and can be seen at the Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam (Netherlands).

- Its position-relation to the theme: The Face of War (The Visage of War; in Spanish La Cara de la Guerra) (1940) is a painting by the Spanish surrealist Salvador Dalí. It was painted during a brief period when the artist lived in California. The trauma and the view of war had often served as inspiration for Dalí’s work. He sometimes believed his artistic vision to be premonitions of war. This work was painted between the end of the Spanish Civil War and the beginning of the Second World War.

- Short description: The painting depicts a disembodied face hovering against a barren desert landscape. The face is withered like that of a corpse and wears an expression of misery. In its mouth and eye sockets, there are identical faces. In their mouths and eyes, there are more identical faces in a process implied to be infinite. Swarming around the large face are biting serpents. In the lower right corner is a handprint that Dalí insisted was left by his own hand.

- Location and European dimension: The painting is located in Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam, Netherlands

- Possible educational exploitation: Salvador Dali has a very interesting style of work. What is unique for his paintings and artworks? How is his work different to the other pieces of art during this protest art period? Reflect at least on his use of colour, realism, shadowing…

Artwork #4 Pablo Picasso, Massacre in Korea, 1937

This artwork is under a copyright, therefore it is not available in higher resolution. The original artwork can be seen in the Musée Picasso in Paris, France.

- Its position-relation to the theme: Massacre in Korea is the third in a series of anti-war paintings created by Picasso. It was preceded by the monumental Guernica, painted in 1937, and The Charnel House, painted from 1944 to 1945. The title of this painting refers to the outbreak of the Korean War, which had started in the previous year, yet the subject matter is ambiguous, as Picasso does not point directly to a period or location within the composition.

- Short description: The painting may depict an event similar to the No Gun Ri Massacre in July 1950, when an undetermined number of South Korean refugees were massacred by U.S. soldiers, or the Sinchon Massacre of the same year, a mass killing carried out in the county of Sinchon, South Hwanghae Province, North Korea. Massacre in Korea depicts civilians being killed by anti-communist forces. The art critic Kirsten Hoving Keen says that it is “inspired by reports of American atrocities” in Korea. At 43 inches (1.1 m) by 82 inches (2.1 m), the work is smaller than his Guernica, to which it bears a conceptual resemblance as well as an expressive vehemence. Picasso’s work is influenced by Francisco Goya’s painting The Third of May 1808, which shows Napoleon’s soldiers executing Spanish civilians under the orders of Joachim Murat.[6] It stands in the same iconographic tradition of an earlier work modelled after Goya: Édouard Manet’s series of five paintings depicting the execution of Emperor Maximilian, completed between 1867 and 1869. As with Goya’s The Third of May 1808, Picasso’s painting is marked by a bifurcated composition, divided into two distinct parts.

- Location and European dimension: The painting is exhibited in the Musée Picasso in Paris.

- Possible educational exploitation: Use the image to discover which other artists created artworks with similar perspective, colour and meaning. Perhaps have a look at the L’execució de l’emperador Maximilià de Mèxic (1868), Edouard Manet to start with. What is different in Manet’s work compared to Picasso’s? Gender? Colour usage? Style – cubism, modernism? What about the work of Francisco de Goya?

Artwork #5 David Alfaro Siqueiros, Torment and Apotheosis of Cuauhtémoc (detail), 1950-51

- Its position-relation to the theme: The Mexican muralist movement began soon after the Mexican Revolution, which took place from 1910 to 1920. After the revolution, the government took on the very difficult project of transforming a divided Mexico. During this time, there was a concern with defining Mexican identity thus the government sought to establish a brand-new Mexican society founded on its rich tradition but very much forward looking. They also wanted a way to promote pride and nationalism in the Mexican people. From all these desires the muralism movement arose. The movement began as a government funded form of public art, they commissioned artists to create art that would illustrate Mexican history. Since most of the population was illiterate, the Mexican government went with murals as an effective way to spread the message of pride and nationalism visually.

- Short description: In “the Torment of Cuauhtémoc”, Siqueiros depicts the violence that came with the Spanish conquistadors, it shows the Spanish torturing the Aztec emperor, Cuauhtémoc, to get him to indicate the location of where the treasure of Montezuma was hidden. They tortured him by burning his feet, yet he shows no physical pain but rather an emotional pain. Beside Cuauhtémoc, there is a man that is crying and praying as if to get out of such punishment. To the right, there is a female that seems to be covered in blood; she also resembles the mother of Jesus when her son was being crucified, begging for her son to stop feeling such torture.

This makes Cuauhtémoc seem godlike and as a symbol of patriotism, a symbol that would be used after the Mexican revolution in many works of muralists at the time. Using the last Aztec emperor as a symbol, allowed for the past to be brought back, inspiration waiving in to push Mexicans to fight for their roots.

The Spanish army looks like they are not human, as if only empty shells with no souls; such lack of humanity allows them to continue doing the damages that they committed. There is also a dog that seems to bring a bit of a conclusion that they are as human as the Aztecs were, it shows how they are rabid animals like such canine they have on the side.

- Location and European dimension: The painting is located in the Museum of the Palace of Fine Arts

- Possible educational exploitation: In the “Apotheosis of Cuauhtémoc”, the “what if?” question comes to be. Siqueiros shows what it would be like if Cuauhtémoc’s army had defeated the Spanish army if they had succeeded with power and strength to keep invaders off. Learners analyze the details of the painting and at the difference of style and techniques between this painting and the painting of Salvador Dali and Pablo Picasso. Look at their portrait and drawing of human figures – work, the colours, the perspective of drawing, etc.

Artwork #6 Golden Rule, Norman Rockwell, 196

- Its position-relation to the theme: In the 1960s, the mood of the country was changing, and Norman Rockwell’s opportunity to be rid of the art intelligentsia’s claim that he was old-fashioned was on the horizon. His 1961 Golden Rule was a precursor to the type of subject he would soon illustrate. A group of people of different religions, races and ethnicity served as the backdrop for the inscription “Do Unto Other as You Would Have Them Do Unto You.” Rockwell was a compassionate and liberal man, and this simple phrase reflected his philosophy. Having traveled all his life and been welcomed wherever he went, Rockwell felt like a citizen of the world, and his politics reflected that value system.

- Short description: From photographs he’d taken on his 1955 round-the-world Pam Am trip, Rockwell referenced native costumes and accessories and how they were worn. He picked up a few costumes and devised some from ordinary objects in his studio, such as using a lampshade as a fez. Many of Rockwell’s models were local exchange students and visitors. In a 1961 interview, indicating the man wearing a wide brimmed hat in the upper right corner, Rockwell said, “He’s part Brazilian, part Hungarian, I think. Then there is Choi, a Korean. He’s a student at Ohio State University. Here is a Japanese student at Bennington College and here is a Jewish student. He was taking summer school courses at the Indian Hill Museum School.” Pointing to the rabbi, he continued, “He’s the retired postmaster of Stockbridge. He made a pretty good rabbi, in real life, a devout Catholic.

I got all my Middle East faces from Abdalla who runs the Elm Street market, just one block from my house.” Some of the models used were also from Rockwell’s earlier illustration, United Nations.

- Location and European dimension: Golden Rule and United Nations are currently on view at Norman Rockwell Museum.

- Possible educational exploitation: Explore the facial expressions and features of all the included pictures in the artwork. Knowing that this piece was created in the 1960s and you living currently in the 2020s, more than 60 years later, would you argue that this artwork is still representing the United Nations. Why (not)? And what could be missing? Try to recreate this piece of work with photos from those around you. Note: Keep an eye out on the lightning when you do photography!

Artwork #7 Guernica, Pablo Picasso, 1937

- Its position-relation to the theme: Picasso painted Guernica at his home in Paris in response to the 26 April 1937 bombing of Guernica, a Basque Country town in northern Spain which was bombed by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy at the request of the Spanish Nationalists. Upon completion, Guernica was exhibited at the Spanish display at the 1937 Paris International Exposition, and then at other venues around the world. The touring exhibition was used to raise funds for Spanish war relief. The painting soon became famous and widely acclaimed, and it helped bring worldwide attention to the Spanish Civil War.

- Short description: Guernica is a large 1937 oil painting on canvas by Spanish artist Pablo Picasso. It is one of his best-known works, regarded by many art critics as the most moving and powerful anti-war painting in history.

The grey, black, and white painting, which is 3.49 meters (11 ft 5 in) tall and 7.76 meters (25 ft 6 in) across, portrays the suffering wrought by violence and chaos. Prominent in the composition are a gored horse, a bull, screaming women, a dead baby, a dismembered soldier, and flames.

- Location and European dimension: It is exhibited in the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid.

- Possible educational exploitation: It is interesting to compare this artwork with the Massacre in Korea. An in-depth analysis in the main characters, colors and colors theory could be a good exercise.

Artwork #8 Serve and Protect, Gregory Ragland, 2013

Red Paint was added by unknown protester(s) during #BlackLivesMatter Protests on the 29th May.

- Its position-relation to the theme: Serve & Protect, demonstrates the sign language ― to serve. The same graceful hands which serve us are also hands strong enough to protect and care for us. This bronze sculpture reinforces the longevity of the force and acts as a powerful symbol of our confidence in those individuals. This powerful and elegant sculpture is a solid reminder that our larger than life heroes will be there to serve and protect us all.

- Short description: Park City artist Greg Ragland created a bronze sculpture titled “To serve and protect.” The sculpture depicts two hands side-by-side with their palms facing upward. The work is located in the plaza garden and designed to encourage touching and climbing.

- Location and European dimension: The painting is located at the Public Safety Building; 475 S 300 E; District 4

- Possible educational exploitation: In his sculpture work, Gregory Ragland did not include the red paint. The original does not include anything on the hand. When did this red paint occur on the sculpture? Observe the changes around this artwork.

Artwork #9 Clenched Fist, Everett Spruill

- Its position-relation to the theme: A symbol of power, the clenched fist is an important symbol of the movement. The colour of the first also hints to which movement it was initially related to.

- Short description: Original hand-pulled serigraph by African – American artist Everett Spruill features a colourful abstract design of a black clenched fist created in a cubist motif. Medium: Mixed Media.

- Location and European dimension: Spruill’s art has been sold at Disney’s Epcot Centre.

- Possible educational exploitation: Experiment using mixed media to create your own symbol of resistance art. Why did you choose this specific symbol?

Artwork #10 Willie Bester, Prime Evil, 2015

- Its position-relation to the theme: Willie Bester is one of South Africa’s most well-known artists who originally began as a resistance artist. Bester currently lives in Kuilsrivier, South Africa

- Short description: Using materials assembled from garbage, Bester builds up surfaces into relief and then paints the surface with oil paint. His works commented on important black South African figures and aspects important to his community. South African resistance artists do not exclusively deal with race nor do they have to be from the townships.

- Location and European dimension: This painting is now located in the Melrose Gallery.

- Possible educational exploitation: The atmosphere and feeling coming off from the artwork are very special. It can be interesting to analyse it comparing it to other artwork of his to see how different materials, their positioning and colours can make such a big difference.

Practical activities

Activity 1

A painting based on a poem

Aims

To connect the learners with the author’s personal story about war times and allow them to express their vision on art

Materials

- Mobile device / computer

- Internet connection

- Canvas

- Painting tools

Preparatory stage for educators/mediators

Give the learners information on the topic of protest art and show them some examples throughout the days and seasons. This will help the learners to understand what the idea and vision was of the artists which created the work during the years.

Development

Ask your learners to watch this video where Rafeef Ziadah a Canadian-Palestinian spoken word artist and activist, shares a poem she wrote about the bombers in Palestine. Once they have listened to this poem – “We teach life, sir”, ask them to create their own artwork reflecting on the scenery she is describing in the poem.

Rafeef Ziadah – ‘We teach life, sir’, London, 12.11.11

Activity 2

Resistance Art, Activist Art and Pop Art

Aims

For learners to discover more specifics about the different art styles and how they have influenced each other and are intertwined.

Materials

Access to a computer with an online connection.

Preparatory stage for educators/mediators

Have a look at the history around artist Keith Haring.

You can use the following links:

Pop art politics: Activism of Keith Haring

Art Activism: Keith Haring — Art History Kids

Keith Haring: Activist and Artist

7 Reasons Why Keith Haring’s Legacy is Still Important

Development

Learners can explore more about an artist through these websites, and then critically reflect on whether Keith Haring is part of the Pop Art or Protest Art movements. Why? Can he belong to both? Could he have been influenced by Protest art and applied the principles in Pop art? How is art different than those of the artists in protest art movement?

Optional: Try to recreate one of his pop artworks, using the method of “stamping”. Good luck!