Introduction

In this dossier, we will cover the theme of the human body in art and its context within Europe. We will look at 10 examples of the human body in European artworks, and we will present two classroom activities – one for learning the principles of gesture drawing, with a bonus activity of drawing the human body using artistic techniques from one of the periods studied. The other will be a lesson and a reflection on the whitewashing of art in Europe.

The objectives of the dossier are to:

- Compare and contrast the human body in European art throughout the centuries, beginning with the Greek Classical era (480–400 BC). We will also briefly discuss the following periods:

- The Archaic period, 600–480 B.C

- The Hellenistic period, 323–150 B

- The Medieval period, 300 CE to 1400 CE, including the three major parts — Early Christian, Romanesque and Gothic.

- The Renaissance, 1400 to 1600 CE

- Impressionism, late 19th century

- Cubism, early 20th century

- Identify key elements and themes of the human body in art

- Summarize the evolution and significance of the human body in art

- Draw the human body using one of the fundamental design elements of a certain art period

- Learn about and reflect on the lack of diversity in European art in terms of the human form and what can be done to solve it.

European background

We have chosen the theme of the human body for this dossier for three primary reasons:

- The important role the human body has played in the evolution of European art and artists.

Artists in Europe have always been fascinated by the human body. Even the earliest examples of ancient Greek art depicted the human form. We can’t talk about the human body in European art without recognizing the influence of the ancient Greeks. The Greeks idealized the human body, bringing it closer to the perfection of the gods. This idealism has very clearly been passed down, and indeed is the driving force behind our contemporary canons of beauty. The nude body has also become an essential skill for European artists to master, with figure drawing being a foundation for any aspiring artist’s studies.

- How the human body has shaped our aesthetic ideals.

When we study the human body as it is depicted in art throughout Europe’s history, we understand the culture of our ancestors and thus we better understand ourselves. We can also use this understanding to help combat negative stereotypes associated today with the imperfect body, by becoming more aware of where this idealism comes from.

- How the human body in art is influenced by racism and how it influences inequalities in society.

The status quo for European art is white artists (usually men) and white subjects in their artwork. The reality is far from the truth, as there have been many artists of different ethnicities throughout the centuries, but European art has been largely whitewashed.

© The Trustees of the British Museum – Source

The theme

The human body plays a critical role in how we understand sexuality, race, ethnicity, culture, gender, and our own mortality.

Sexuality and gender

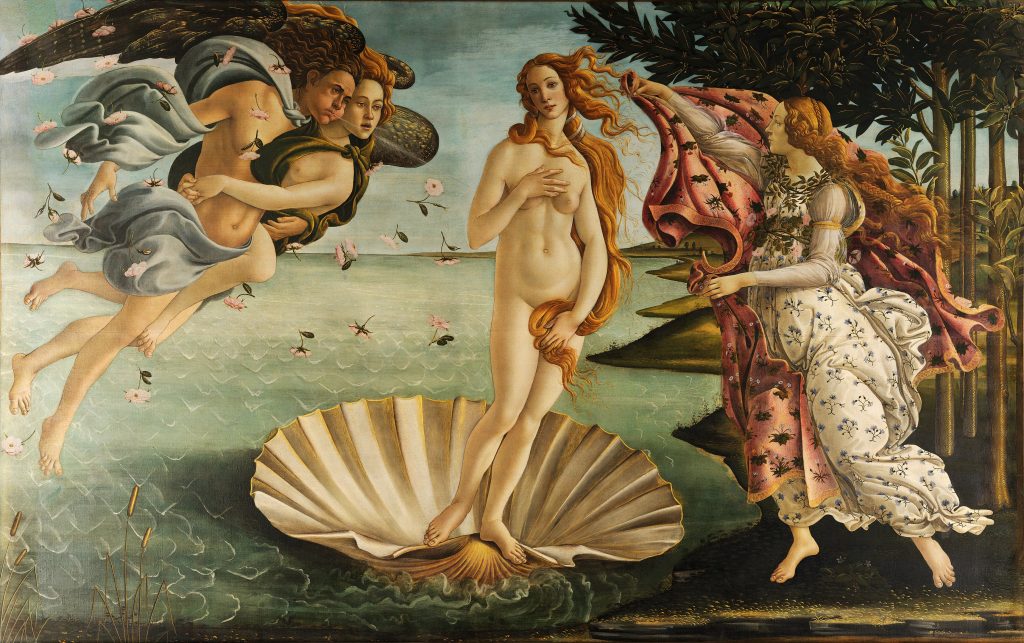

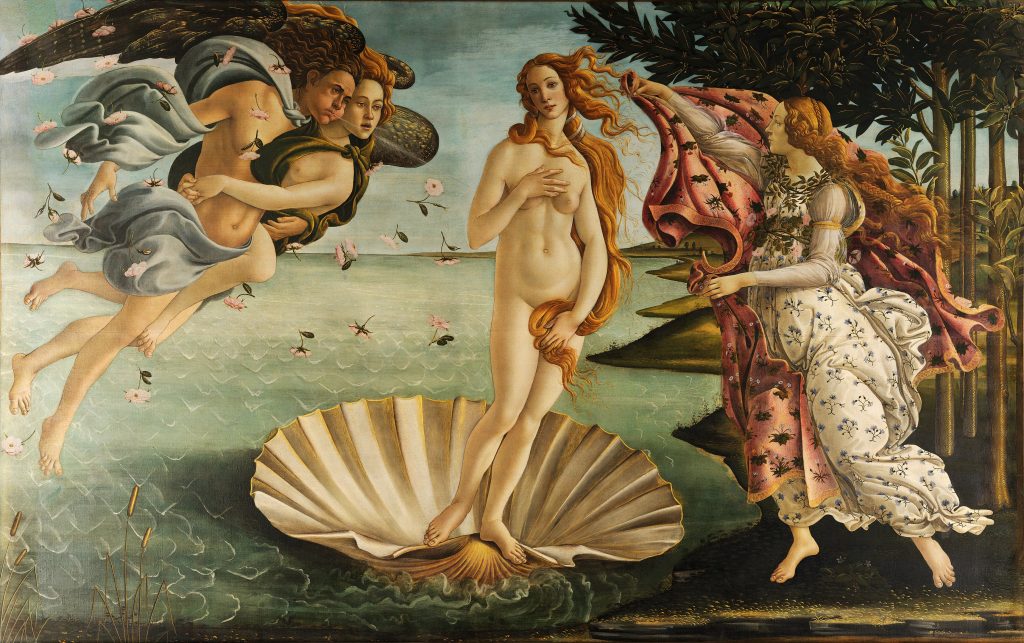

Since the return of the female nude to Western art in 1486 with The Birth of Venus by Sandro Botticelli, it was normally male artists depicting female nudes, and typically for primarily male viewers. These female forms were often idealized, and they not only served the purpose of art but idealized erotic figures.

According to art critic John Berger in his manuscript, Ways of Seeing, post-renaissance European art often depicts nude figures from the front, which allows the protagonist of the sexual encounter to be the viewer.

This is a contrast from how female nudes were depicted in Ancient Greece where the male nude was predominant. If a woman was unclothed in art during that time, usually one hand was kept covering her genitals. The covering hand serves two purposes— it pretends modesty but also serves to draw one’s eye to the hidden spot.

Race and ethnicity

Non-westerners are rarely depicted in the popularized European art, and when they are they might be depicted with exaggerated features, or as a subordinate to the white protagonist. This is not to say that there weren’t artists of color and that there weren’t more artwork that featured people of color as the protagonists. It is, however, to say that white people hold more privileged positions in the European art world, and they have for many centuries, so they’ve been the ones deciding which artwork would be considered worthy.

Mortality

Art in ancient Greece idealized the human form to bring it closer to that of the gods. This suggests a desire to be less mortal, and more immortal. Later on, during the Christian art period, the human body was depicted in religious scenes, suggesting, if not a desire to be immortal, a desire to be seen worthy of god’s love, which in the end allows you entrance to heaven, which is in itself a type of immortality.

Further considerations

- People have always modified their bodies, with piercings and tattoos or diet or exercise.

- The shape of human bodies has been a means of determining someone’s socioeconomic standing in various ways across cultures.

- The human body in art symbolizes everything from religion, to politics, to identity, good and evil, pious and sinner, to the more obvious standards of beauty.

- Historical and geographical context in the country, in Europe, or world-wide: historical events of the time, geographical borders, movement of persons and any other relevant background information.

Ancient Greece

Archaic Period 600–480 B.C.

The human form in Contemporary western art can trace many of its roots back to Ancient Greece. In the 6th century BC, capturing the human body in art became a focal point, with new techniques allowing artists to depict the body in more realistic ways.

The 6th century was the beginning of the Archaic period of Greek art, which lasted from 600 to 480 BC. This was a time of constant evolution in technique, with more naturalistic appearances of the human body. The Greeks considered the body to be an expression of the inner being, directly connected to the mind. So to represent the human figure perfectly meant that the human being represented also had a perfect mind. During the early part of the Archaic period, there is still direct influence from Egyptian art.

Only Greek men were portrayed nude, a reflection of how they were presented in society. There are only a few sculptures of women from the period that exist today, and all show the women fully clothed, and looking directly at the viewer. Human sculptures during the Archaic period also feature the Archaic smile, no matter what activity they were engaged in.

Classical Period 480–400 B.C.

During the Classic period, the sculptures of humans take on their own agency. They stop looking directly at the viewer and instead look off into the distance as if thinking. The figures stop being so rigid and instead take on a sense of weight and fluidity. Now is when we see the introduction of the contrapposto, when the figure is standing at rest, the body’s weight shifted to one leg. The Greeks also used proportions to create idealized figures, skewing the sizes of certain body parts to show ideal proportions. The Archaic grin disappeared as well, and sculptures took on more noble, serious expressions, a more candid approach instead of smiling directly at the ‘camera’.

Hellenistic 323–150 BC

There was a cultural revolution of sorts after the death of Alexander the Great. Cities grew and demanded more and better art. Hellenistic art emerges, dripping in emotion, violence, sensuality. Hellenistic sculptures portrayed what they saw. The god-like figures from the classical period are no more, sculptures are shown instead with their imperfections.

(c. 230-220 BC) by Epigonus, Rome. Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license. Author: Antmoose

Hellenistic sculptures have lots of detail and all used the following elements:

- Shape: The muscles beneath the skin are very detailed, as are facial expressions, resulting in easy-to-read emotions. Hair also takes on more volume and weight, whereas before not much attention was dedicated to it and it was flat.

- Composition: Rigid stances are replaced by everyday poses, with S and C curves.

- Texture and pattern: Detailed hair makes for exquisite texture. These sculptures would have been painted as well in lots of detail.

Medieval Art 5th–14th century

Medieval art in Europe was dominated by the rise of Christianity, and saw the disappearance of nudity almost entirely from art. The only nude people in art were Adam and Eve, and they served as a symbol of the original sin. Additionally, during this time, the human body wasn’t related directly to the real world, and thus wasn’t very realistic.

Early Christine Age 5th–7th centuries

The Catholic Church was gaining influence, and in 350 CE had two main power centers, Rome and Constantinople. Art was used for decoration and public appreciation. It was also used in houses of worship. The art of this period had roots in classical Roman style, which was based on the classical Greek style but was more abstract and simplified. The purpose of the depiction of the human figure was spiritual instead of physical beauty. The faces had large staring eyes referred to as the ‘windows of the soul’.

Romanesque 11th–12th century

The Romanesque period lasted from the second half of the 11th century through the 12th and is the first international style of art. Thanks to increased travel, it reached across the Mediterranean and up to Scandinavia. Human forms became more expressive in the Romanesque period than they were in the Early Christian period. They often had elongated figures, there was a focus on linear and decorative details like clothing folds and hair, but realism wasn’t the focus. Often the human figure was sculpted and featured in architectural reliefs, especially during the 11th and 12th centuries. Most sculptures of humans were pictorial and biblical.

Gothic 12th–16th centuries

In the Gothic period, the human figure was represented more naturally with a life-like appearance, compared to the Romanesque period. Later Gothic figures become much more realistic, with natural expressions on their faces and care to accurately represent the folds of clothing.

Renaissance 14th–17th centuries

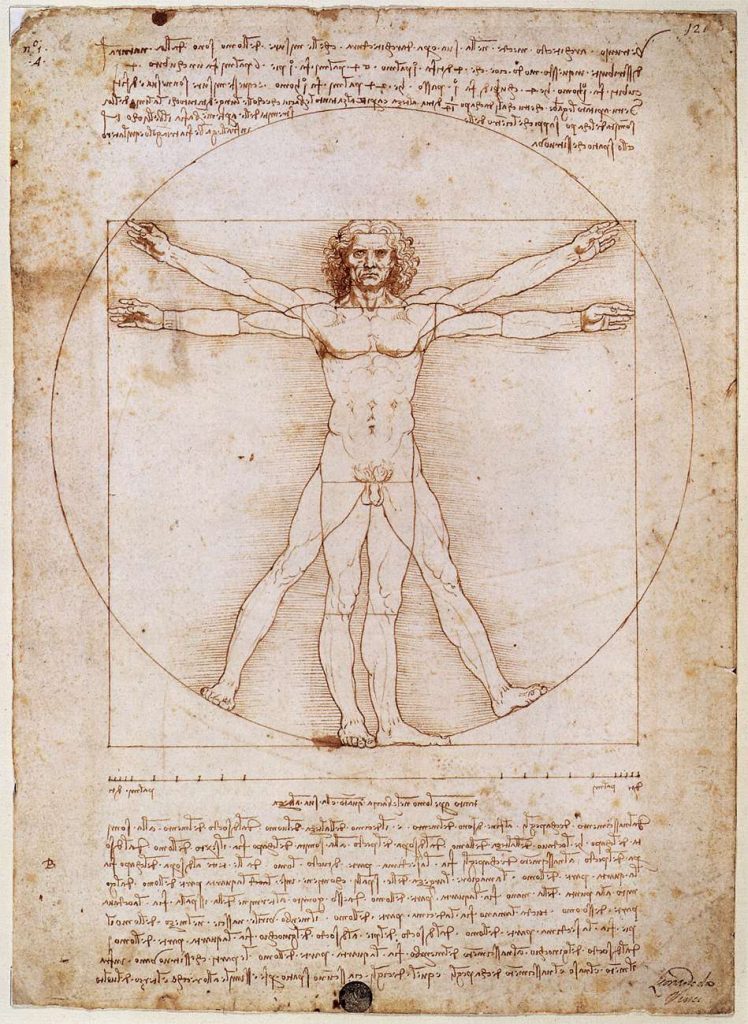

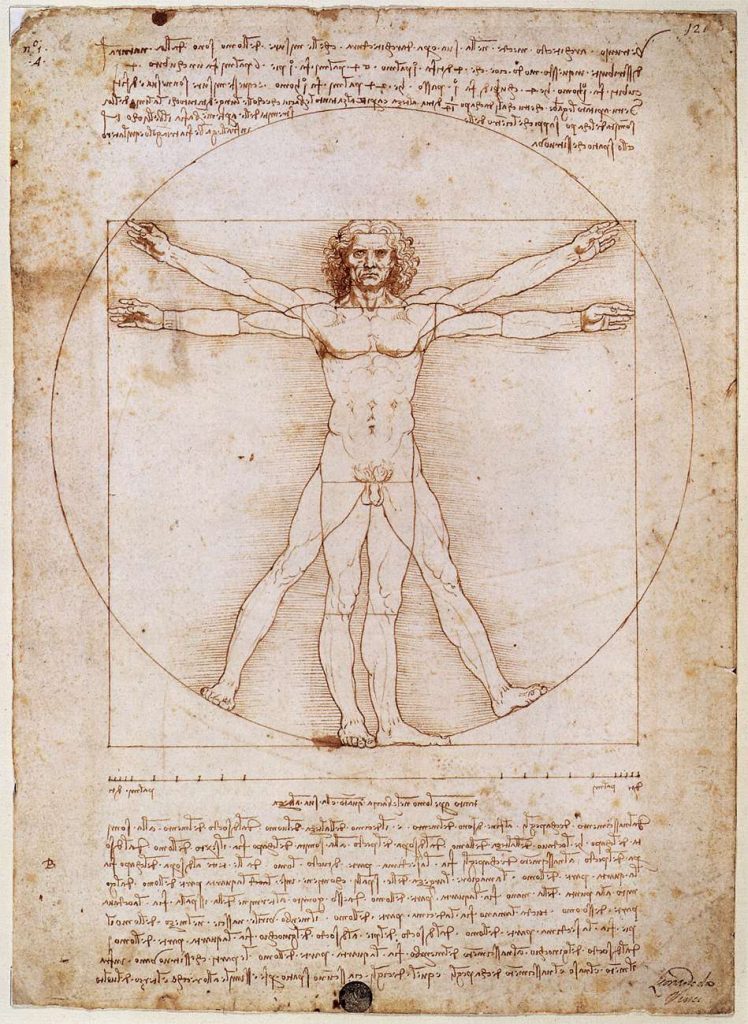

The Renaissance brought about a much greater focus on the human body, and in a much different way than the medieval period. While the body was depicted in an abstract, two-dimensional manner that had the effect of making the figure seem less connected to its human self, the renaissance artists drew their inspiration from the more realistic ancient greek and roman sculptures. They returned to the mathematical ratios that Roman authors Pliny and Vitruvius spoke about, and as you can see in da Vinci’s The Vitruvian Man.

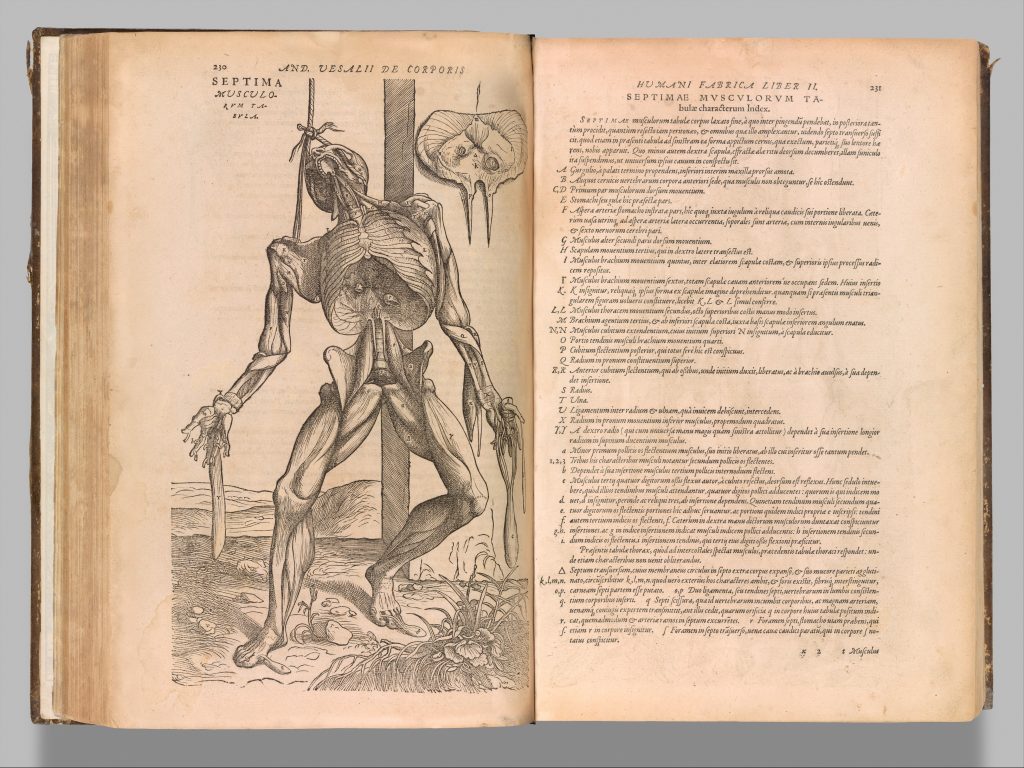

Aside from classical depictions of the human form, artists during the Renaissance became experts in anatomy as they worked to make their portrayals of the human figure even more lifelike. These artists knew much more about anatomy than did students studying anatomy at the university.

Both da Vinci and Michelangelo were known to do detailed anatomical dissections, setting a new standard for the portrayal of the human figure. Art patrons came to expect perfection in anatomy.

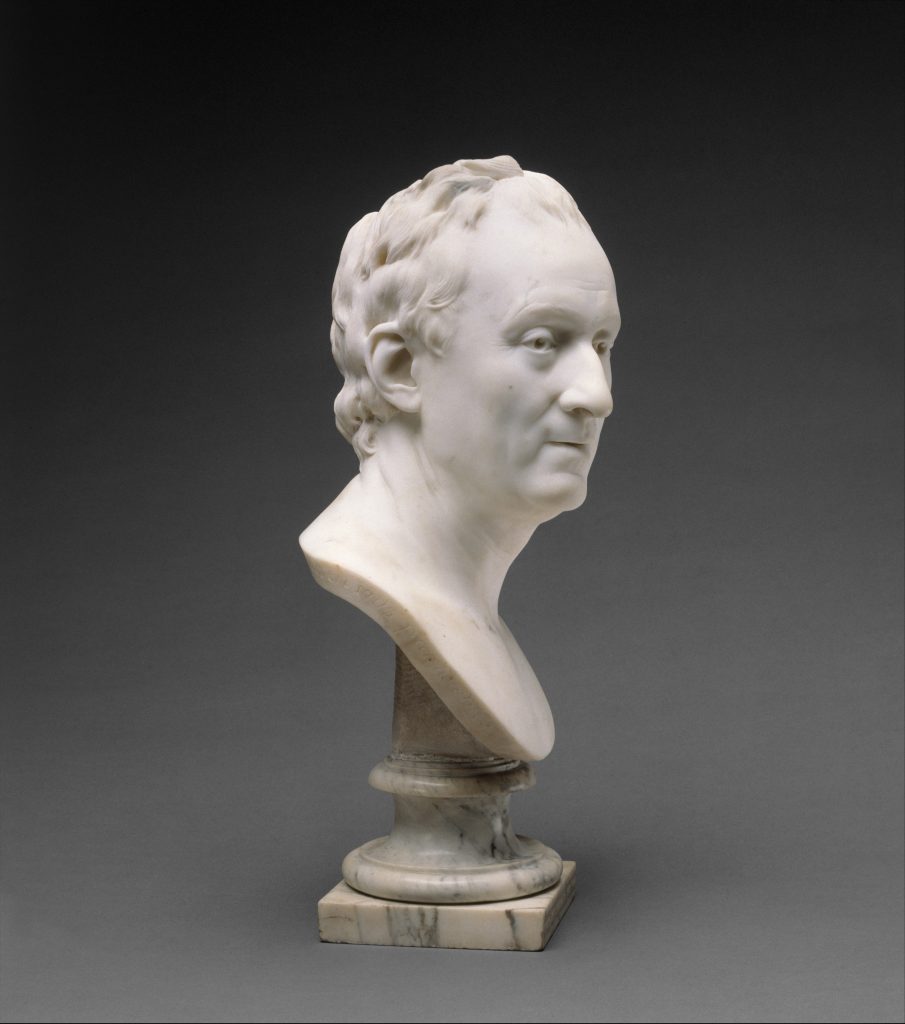

Neoclassicism 1750–1850

The artists of the Neoclassic period were also inspired by ancient Rome, especially when it came to the depiction of cloth draped on the human figure. This period is considered to be a revival of Greek and Roman art and is closely tied with the Age of Enlightenment which took place from the 17th century to the 19th century. This period was founded in philosophical thought, with reason a leading force in morals. It was also influenced by the Scientific Revolution, which developed at the end of the Renaissance, and one of the themes of this period was anatomy, which figured greatly into art.

People in Neoclassical art were depicted with a sense of ‘noble simplicity” inspired by the ‘quiet grandeur’ of ancient Greek sculpture. The neoclassical sculpture showed life-sized figures and portrait busts (like those by Jean-Antoine Houdon, 1741-1828). Sculptures often depicted their subject with much realism, the terms used were ‘verism’, or the more glib ‘warts and all’. This was also used in Roman sculpture, and it meant that the artist should include all of the imperfections seen on the body, including warts and wrinkles.

Impressionism late 19th century

Artists like Edouard Manet begin to break from the boundaries of drawing the classical nude, to drawing nudes from real life, with anatomical effects and disproportions that only a live model would have. This was the beginning of impressionism and influenced artistic creation beginning in the 20th century. Artists like Renoir and Degas kept with the anatomical resemblance of the actual live model, as well as drawing the nude within a composition, giving it the same weight as the surrounding decor.

Cubism early 20th century

Cubism artists turned their backs on three-dimensional representations of the human form, and instead flattened and fragmented the human body into geometric forms with a 2-dimensional aspect. Picasso and Braque lead the movement, with multiple points of perspective and monochromatic colors along with mixed media.

The artistic context

The human body has always been a primary source of inspiration for artists, across geography, religion, culture and socioeconomic level.

The human body has represented beauty, sex, it has caused great controversy, it has been prohibited. The oldest cave painting is a human figure, showing that even the earliest humans were fascinated by their own bodies and wanted to represent them artistically.

In Greece the human body was idealised as athletic; in Christianity the body represented suffering and piety; during much of Islam it was frowned upon.

In conclusion, when we consider the human body in the history of art, we raise questions about cultural, sexual, socioeconomic and ethnic identity.

The social and political context: the artists are influenced by the political organization, social organization, major issues of the time they are creating in. On the other hand, art influences the audience; it may evoke particular emotions or moods, for social inquiry and political change, for questioning and criticizing society, or as a means of propaganda or commercial advertisement for influencing popular conceptions.

Art, along with religion and government, determines how we act as a society; and very often art, religion and government interact and even overlap. Some important questions to ask regarding art and its social and political context include:

- How does art affect how we live?

- How does art change the way we see ourselves?

- How does art change the way we feel about religion and politics?

- Can art really be used as a tool to govern?

- Have governments or religions ever used depictions of the human body in art to shape their constituents through their gaze? And what are/could be the implications?

Pedagogical approach

Why is this theme relevant to adult learners?

Adult learners will explore how the representation of the human body through art has impacted society, politics and self-image throughout human civilization. By understanding the meaning behind such works, adult learners will view society through a different lens, and will learn more about why we are who we are, why we think like we do, and why we consider some bodies to be more beautiful than others.

What are the learning outcomes of embedding this cultural/art theme with an educational activity?

The human body is one of the most classic models for artists. There is much to be learned from both seeing the human body depicted in art (including societal context, political meaning, and beauty standards) and adult learners will learn a wide range of techniques and skills by learning to draw the human body. Thus the learning outcomes are:

- Consideration of why we consider some bodies to be more beautiful than others

- Knowledge of the various ways that the body in art has been used as propaganda, by governing bodies and how it has changed society;

- Anatomical knowledge of the human body and techniques for drawing

- How to recognize the evidence of prejudices, marginalized groups and racism through artwork

How to do it: strategies, tools and techniques.

Adult learners will study the history behind specific artworks that depict the human body over the ages, and will also create their own representations of human bodies.

Artworks

Artwork #1 The Birth of Venus, Botticelli, 1480 (Renaissance)

- Its position-relation to the theme: Relates to the ideal of feminine beauty at the time. Her depiction as a nude is significant in itself, as during the Renaissance history almost all artwork was of a Christian theme and nude women were hardly portrayed.

- Short description: Straightfoward meaning – The goddess of love and beauty arriving on land standing on a giant shell. She is helped by the winds and is surrounded by flowers, a reminder of spring.

- The Author: His full name was Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi was born in Italy in 1445 and is known as Sandro Botticelli. He was a painter of the Early Renaissance.

- Painted by Botticelli for the Medici family in the 15th century, now located in the Uffizi gallery.

- Talk about how beauty has changed over the years. Compare Botticelli’s painting style with contemporaries.

Artwork #2 The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp, Rembrandt, 1632 (Baroque painting)

- Its position-relation to the theme: Instead of the body being appreciated for its beauty, this is a body in a scientific, perhaps even grotesque context.

- Short description: Nicolaes Tulp explains the musculature of the arm to doctors.

- The Author: Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, known by Rembrandt, was a Dutch painter born in 1606, considered one of the greatest visual artists in history.

- Location and European dimension: Painted by Rembrandt in 1632, now in the Mauitshuis museum in The Hague.

- Possible educational exploitation: Learn about Baroque painting style and drawing techniques for anatomy.

Artwork #3 The Valpinçon Bather, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, 1808 (Neoclassicism)

- Its position-relation to the theme: The painting is of a naked woman.

- Short description: French Neoclassical painting of a ‘bather’, sitting on a bed with back to the viewer.

- The Author: The artist was Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, a French Neoclassical painter born in 1780.

- Location and European dimension: Louvre, Paris

- Possible educational exploitation: Some social themes could be investigated, such as the fact that neither the woman’s face, nor the front of her body are showing. We can also see the evidence of Neoclassical ‘airbrushing’ or erasing any imperfections in her body. The painting can also be used to discuss how to use light, and how the artist was able to make the model appear weightless and other painting techniques.

Artwork #4 Olympia, Édouard Manet, 1863 (Impressionism)

- Its position-relation to the theme: This painting not only deals with female sexuality, but even more notably, depicts the body of a black woman in a manner that subverts the status quo of the time.

- Description: A black maid named Laure wears contemporary French clothing and advises the prostitute Olympia who stairs directly at the viewer.

- The painter, Édouard Manet, was born in France in 1832 and was one of the first 19th-century modernist painters to illustrate modern life.

- Location and European dimension: Musee d’Orsay Paris

- Possible educational exploitation : This painting will allow students to learn about the representation of black women in Europe as well as the representation of prostitutes.

Artwork #5 Head of a Skeleton with a Burning Cigarette, Van Gogh, 1886 (Postimpressionism)

- Its position-relation to the theme: Here we see the human body without flesh and with a humorous aspect.

- Short description: Anatomical study of a skeleton smoking a cigarette.

- The Author: Vincent van Gogh was a Dutch post-impressionist painter born in 1853 who, after dying, became an extremely influential artist in Western art.

- Location and European dimension: Painted by Van Gogh in 1886, currently at Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam.

- Possible educational exploitation: Study anatomy, and discuss if it’s art or just juvenile.

Artwork #6 Marble metope from the Parthenon (South metope XXXI)

- Its position-relation to the theme: This set of carved plaques represent and describe different scenes of famous fights in Greek history and mythology. They are relevant for their representation of all bodies following the ideal canons of the period.

- Short description: This is one of the 92 marble metopes you can see on the Parthenon where many depict a famous battle between the Centaurs, the mythological creatures, and the Lapiths, a mythical tribe in Greek history. Although some were almost fully destroyed over years, some silhouettes and figures are conserved and have been reconstructed. In each side of the Parthenon, the metope represents a different important fight. In this one (South Merope XXXI), we can see a Centaur on the left and a Lapith on the right fighting.

- The Author: Pheidias, in Greek “Φειδίας”, was a either the sculpture or the head of all artists who took part in it. He was a sculptor from Athens and is considered one of the most famous sculptor of ancient Greece. He worked mainly in Athens, in the Parthenon sculptures but he is also well known for his gold and ivory Zeus sculpture, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world.

- Location and European dimension: This piece of the metope can be found in the British Museum; it was acquired in 1816 and it has never returned to its original setting.

- Possible educational exploitation: You can discuss the issue with art belonging to one country being restored and kept in another, something that many countries argue about. You can also have students research a bit about mythological creatures, like centaurs, and how they have been represented as partly human over time, i.e. how much they resemble to human bodies and if that has been represented differently over civilizations.

Artwork #7 Vitruvian Man, Leonardo Da Vinci, 1490 (Renaissance)

- Its position-relation to the theme: This drawing is related to a vision of the time of a proportionate human body and the importance of balance and harmony.

- Short description: This drawing, by Leonardo da Vinci, portrays his idea of the perfect human body, highly proportionate, and has his notes and inscriptions on top and below the drawing. The description belongs to Vitruvius, a Roman architect, engineer and author of “De architectura”, from the 1st century BC, who is known for his idea of “firmitas, utilitas, and venustas (“strength”, “utility”, and “beauty”)” the three features that all buildings should have. It is said that the Leonardo did not only take the measure and proportions from Vitruvius’s work but also he measured many models himself. Although the measure were taken as the ideal body for many years, they have been questioned lately.

- The Author: Leonardo Da Vinci, born in Italy in 1452 and known not only for his paintings and drawings but also for his knowledge, notebooks and notes on anatomy, astronomy, botany, and cartography among others.

- Location and European dimension: It can currently be found at Gallerie dell’Accademia, in Venice, Italy, and it has been of great importance in the art world for the way it blends mathematics, geography, art, the human body, and, to some extent, nature.

- Possible educational exploitation: You can do a group activity measuring several people from the group and drawing them following this style. Then you can compare all drawings and have a short debate about human body canons, standards and proportions.

Artwork #8 Wounded Man Panel, -20 000 ; -12 000 (Rupestrian Art)

- Its position-relation to the theme: It is an important artwork because in that period paintings mainly represented large animals and no human figures. Also, because of the strong relation with shamanic practices and with the sexual organs of the human body.

- Short description: It dates back to the Paleolithic. It is between 17,000 and 16,000 old. The painting is located in a separate part of the cave called The Shaft, which was probably a special or hidden place in the sacred Lascaux caves. The main representations in the painting are an injured man, a wounded buffalo and a rhinoceros. The most important part shows a man with a bird head and a bison. The only man in the scene man is lying injured by the animal next to him. Some think that he might be a hunter while others think he might be a shaman for all the shamanistic and totemistic elements. He is wearing a bird mask, his hands remind us of bird feet, and his phallus, erect, is pointing at the pierced bull.

- Location and European dimension: This wall painting is located in a group of caves called Lascaux, near the village of Montignac, in the South West of France. There are more than 600 paintings on the walls and the ceilings of the cave.

- The Author: It is unknown.

- Possible educational exploitation: When dealing with rupestrian art, you can talk about how the roles of men and women were depicted at that period; how nudity was the general rule and research a bit about the evolution of rupestrian art over thousands of years. For example, how at first only animal scenes were painted and how then scenes were people were more common. You can also analyse the techniques used to differentiate male and female bodies.

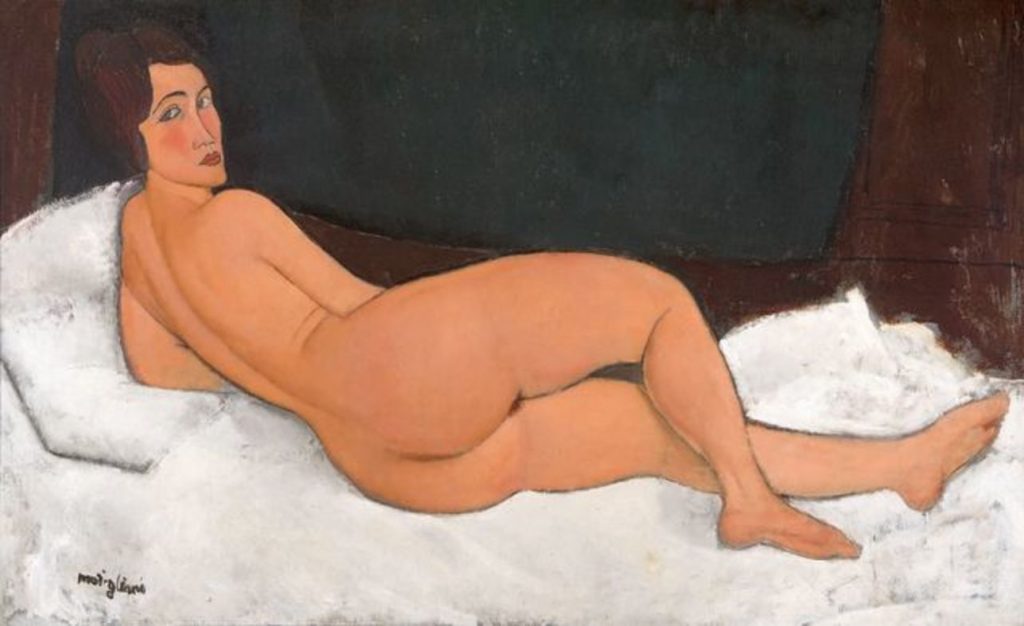

Artwork #9, Reclining Nude, Modigliani, 1917 (Expressionism)

- Its position-relation to the theme: Painting by Modigliani, who often painted sensual, empathetic and emotional female nudes.

- Short description: This painting shows the entire body (turned away from the viewer) of a nude woman reclining on a bed, supported by a cushion. She looks over her shoulder with a confident gaze and bright red lips.

- The Author: Amedeo Modigliani was an Italian Jewish painter born 1884 who worked in France for most of his career.

- Location and European dimension: Painted by Modigliani in Paris, the work is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MoMA), New York City, NY, US.

- Possible educational exploitation: Talk about the controversy surrounding nudes at the time (Modigliani’s first solo show was supposedly closed because of the nudes). Discuss that since his technique appears to be somewhat childish, why is it so good? Learn about the tortured genius that Modigliani was. Is a certain amount of pain necessary to create good art?

Practical activities

Activity 1 – Art and cultural heritage – The whitewashing of European art

- Aims – Talk about racism today and how that is reflected in “European Art”. Discuss the lack of brown and black people represented in European Art and through history.

- Materials – A laptop, computer or tablet per student or per group of students

- Preparatory stage – Listen to this interview before the session and have look at this article to understand the topic a bit better. Choose at least 5 or 6 examples from the article and be ready to display them on a screen with an overhead projector.

- Development – Step 1: the teacher will display on the screen some images in a comparative way to bring up the issue of racism in art. The teacher will ask some questions to encourage some discussion and debate among students. Students will talk about their experiences seeing racial and ethnic diversity in art. Step 2: Students will do an internet search (individually or in groups) and they will have to prepare a short presentation that presents this issue including national and if possible local examples. Then, they will have to try to find museums that make an effort to display art with lots of diversity.

- Handouts or practical sheets – If students have a sufficient level to do so, give them this article (printed or in digital format) about examples of whitewashing. Ask students to come up with more examples

Activity 2 – Draw the human body

- Aims – learn/practice gesture drawing techniques

- Materials – Charcoal, paper, still objects, classmates as models

- Preparatory stage for educators/mediators – teach students the fundamentals of gestural drawing. Teach students how to work with charcoal. Practice drawing on still life objects.

- Preparatory stage – Teachers watch these videos to learn the basics about gesture drawing (they don’t need to be experts on the topic, teachers will only let students experiment with the technique).

- Development – Step 1: Teachers introduce students to gesture drawing (they may use accompanying presentation or videos to do so). Step 2: students will take turn modeling for 5 second intervals while their companions create figure drawings with charcoal. Step 3 Students will then take 2 minutes to draw gestural drawings of their companions. Step 4. Students will pass their drawings around and will discuss the difficulties of gesture drawing and will have a short debate about how this is related to beauty canons of each époque.

- Handouts or practical sheets – Powerpoint introducing gestural drawing like this one.

- Final activity – Each student should choose a technique from one of the periods of European art and draw the human form in that way. For example, classical Greek, Christian art etc.

References

Web

- Why does the art of Ancient Greece still shape our world? (from BBC timeline)

- Greek Art part 1: The human figure, from Geometric to Hellenistic, Francisco Guerrero

- Considerations on the Human Body in European Art from Ancient Times to Present Day

- Neoclassical Art – A Return to Symmetry in the Neoclassical Period

- The Body Hidden, the Body Revealed: Neoclassical Drapery Studies

- Anatomy in the Renaissance

- The Classical Treatment of the Body

- Romanesque Sculpture

- Romanesque Art

- Fragmented: The Human Form in Early Cubism

- The body in Ancient Greek Art

- Sexuality in art

Book

Johan Joachim Winckelmann in his publication “Thoughts on the Iimitations of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture” (1750)